In 1864 Georg I Heinrich Ritter Mautner von Markhof moved to a newly founded factory in Prager Straße 20, Vienna Floridsdorf. In 1872, he bought a mill and, together with his brother-in-law Otto Freiherr von Waechter, expanded the business to include a malt factory, which operated under the name “Waechter & Mautner” and soon became one of the largest in Austria. In 1884, he acquired a small brewery in Leopoldsdorf, but sold it five years later to the Waechter family. After the fire in the mill which was connected to the yeast factory in Floridsdorf, he decided to build his own new brewery in 1892 and invested his proceeds in the foundation of his own beer production, which he named “Brauerei zum Sankt Georg”. The plant went into operation in February 1893. When St. Georg was founded, Adolf Ignaz’s “contract penalty” (to prevent rivalry) to his brother Carl Ferdinand (he ran the St. Marx Brewery), which today is worth about 2.5 million euros and was, of course, paid by mutual agreement, became due.

Georg Heinrich had also decided to brew a beer in Vienna, which did not need to shy away from the comparison with the famous Pilsner Urquell and that he met his necessary requirements “There can be no better beer than ours” which could also be proven subsequently by numerous awards. Within a very short time, St. Georg – after Schwechat, Sankt Marx and Liesing – rose to become the fourth largest brewery in Vienna. His further principles “care and appreciation of customers”, “best understanding and a warm heart for employees and workers” and “only the best raw material was to be used to produce the most excellent product” not only reflect his father’s spirit, but also played a major role in his success. For the first time the opinion that “a light beer of the quality mentioned could only be produced on the spot in Pilsen” was thus refuted. The favourable location in the up-and-coming and densely populated community near the connecting track to the northwest railway behind the brewery also spoke in favour of the start of brewing in Floridsdorf. Floridsdorf would have almost become the capital of Lower Austria if Karl Lueger hadn’t prevailed as Vienna’s mayor and connected it to Vienna.

With the foundation, Georg Heinrich also took a great risk. Specialists advised against that because “Today, when you don’t know in the morning what the evening will bring, new foundations would only play into the hands of the tax authorities” or “Nowadays one should wait tactfully with the founding of breweries and not, at the risk of overloading the money market, at any price to invest the still liquid capital in brewery shares, because this would force dividends artificially at the cost of the beer price or quality, or the stop of the payment of dividends at all”. Source Gambrinus

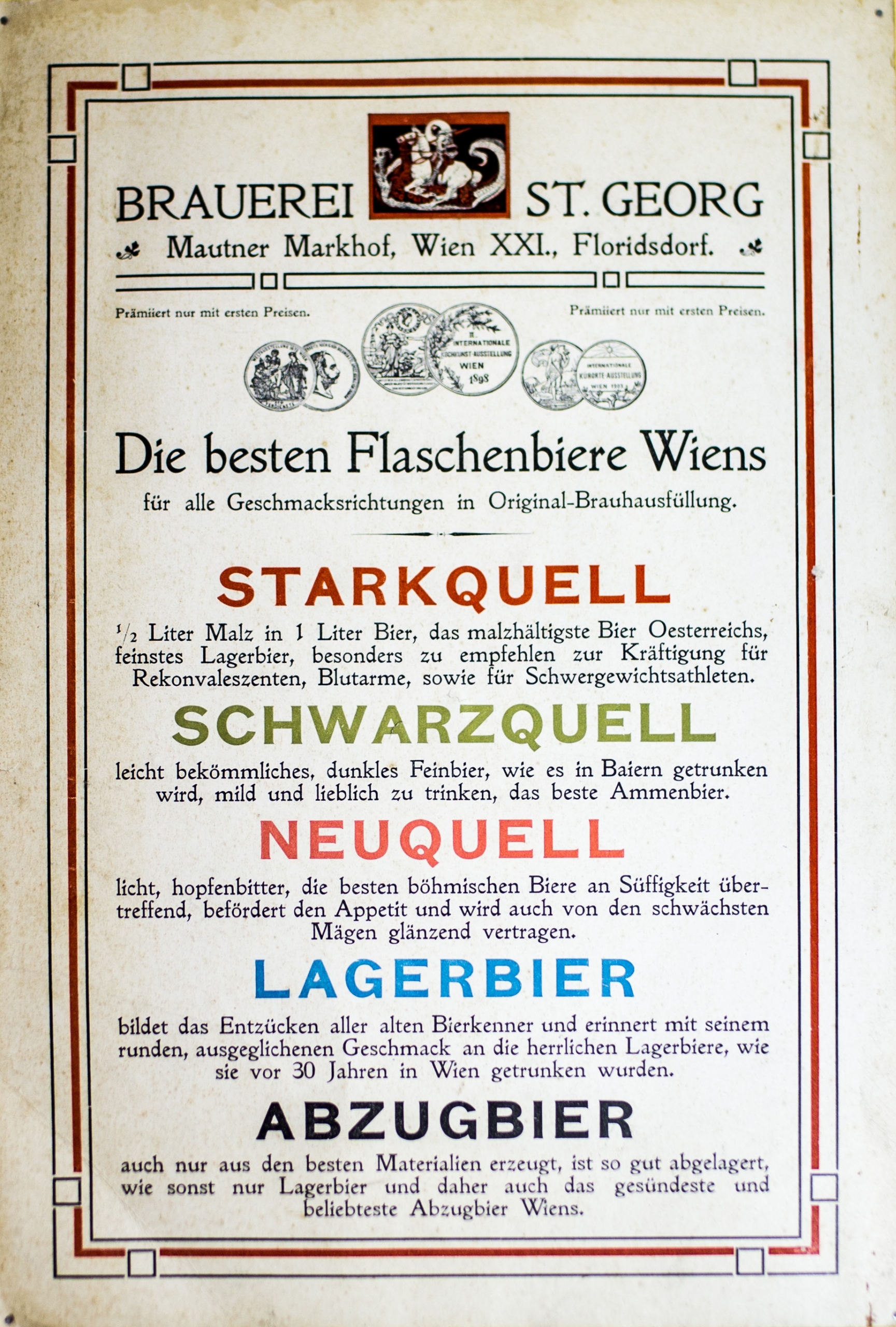

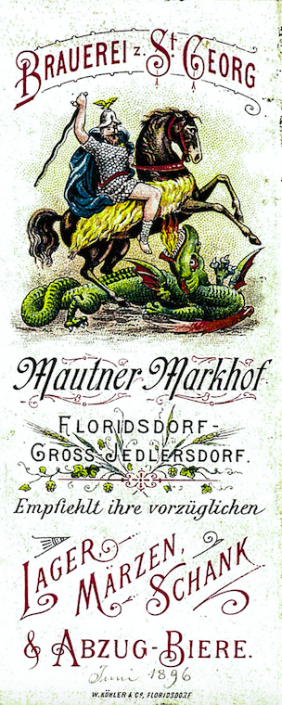

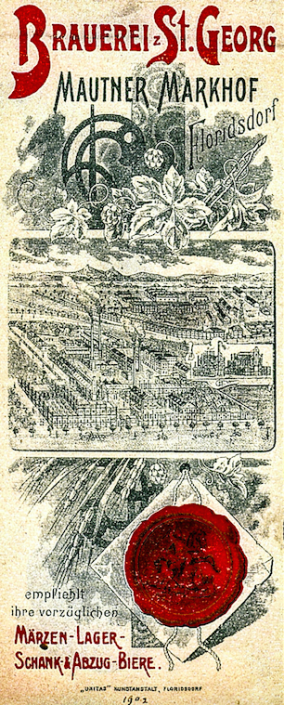

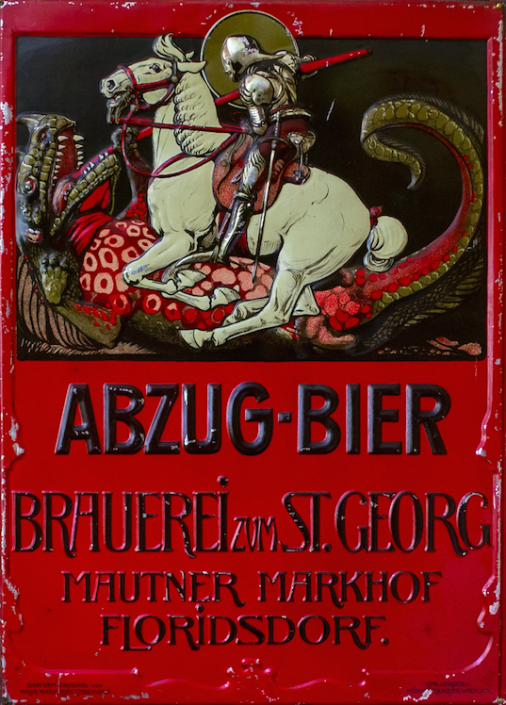

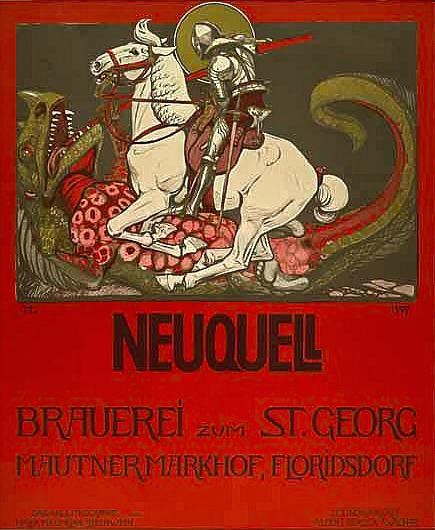

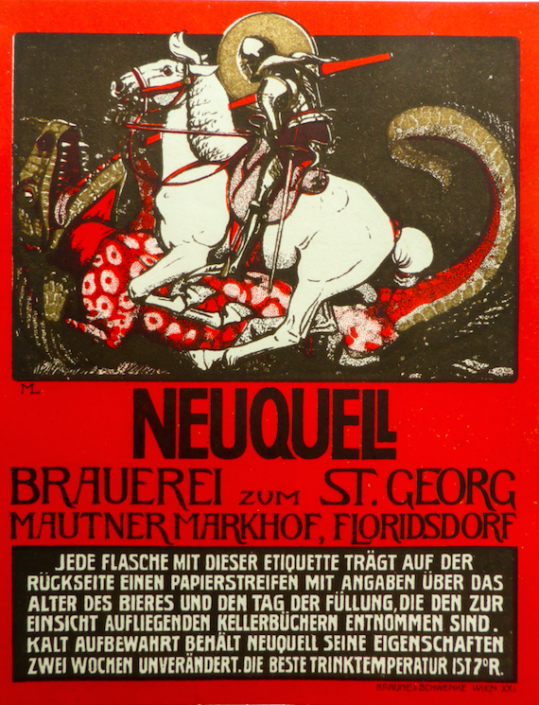

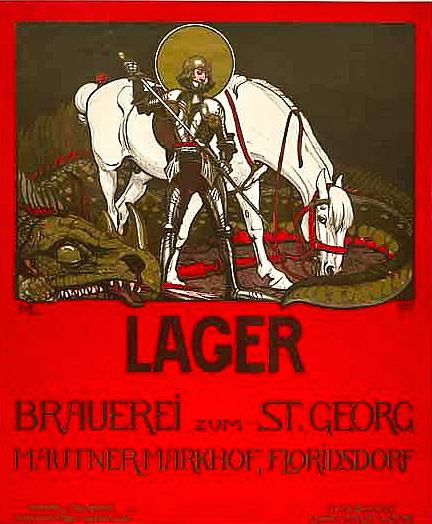

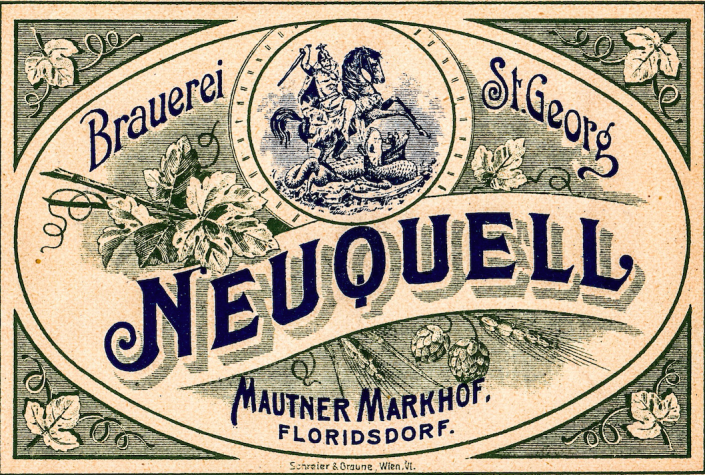

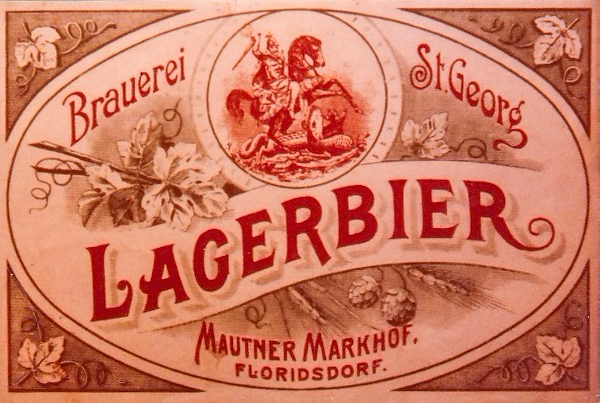

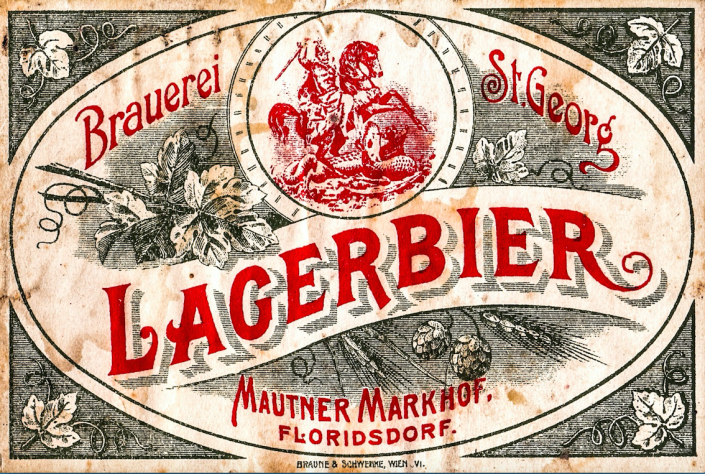

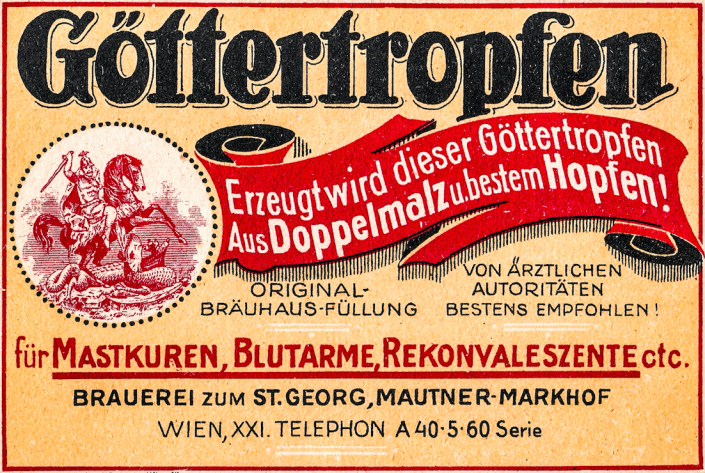

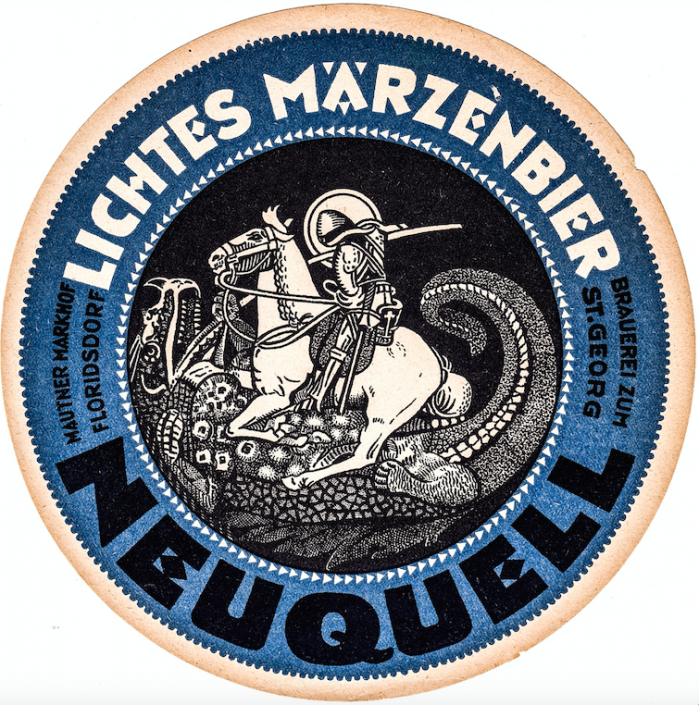

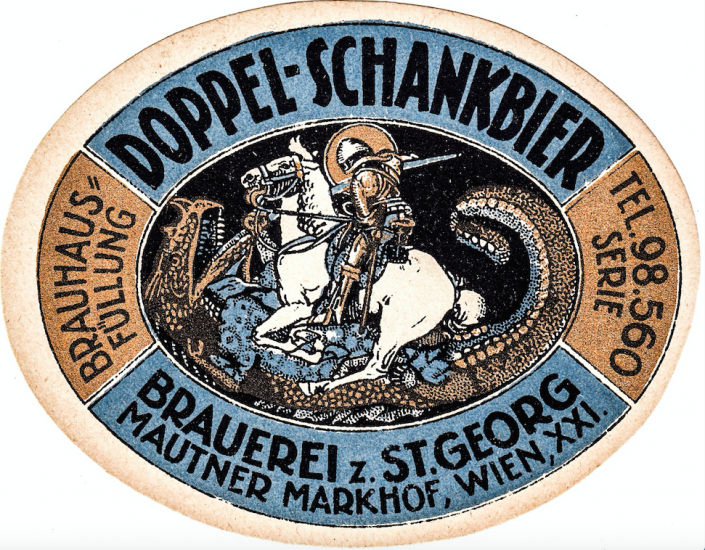

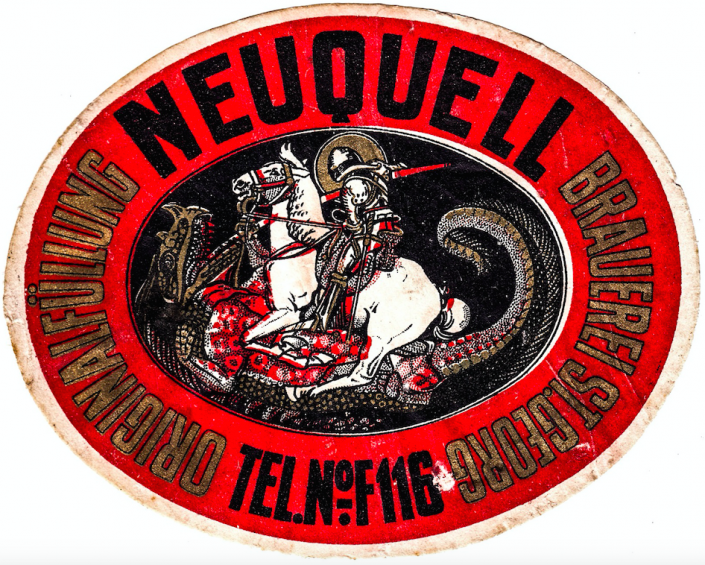

Soon after the brewery was founded, Georg Heinrich and his sons Theodor I and Georg II Anton started to produce three types of beer. The 10 to 11-degree draft beer, a 13 to 14-degree Viennese lager beer and a light, hop-bitter beer brewed like Pilsner beer, which was called “Märzen” beer. That bottom-fermented “St. Georg`s Märzen” beer was soon to become one of the most famous beers in Europe. In addition to the awarding of the honorary diploma at the “International II Viennese Cooking Art Exhibition” in 1898, the highest award for consumers and innkeepers in terms of equality with the Pilsner, the fact that the 200,000 hectolitre mark was exceeded in 1900 (with 31 officials and 300 workers) attested its immense quality and popularity. A success that had never been seen before in the brewery industry within such a short production time. St. Georg was one of the most modern brewing companies of its time, was equipped with the most innovative machines and also had its own block ice production. The peculiarity was the above-ground storage and proofing cellar on the first floor “with the very best ice and other machines”. As they only worked with the best ingredients they soon reached the goal of achieving the same quality as their model beer in Pilsen. However, they initially had to struggle with the expected great financial difficulties and Theodor I recalled that the last guilder was used to build beer deposits from former stables.

The area between Prager Strasse and Peitlgasse was divided into several courtyards and surrounded by a wall. At the entrance to Prager Straße 20 there was a manor house, administration building, sales room, cash desk, yeast production and boiler house. A cafeteria provided fresh food for the employees. In the adjoining second courtyard were the mill, coppersmiths, malt tunnels, workshops and storage cellars. The third courtyard housed cleaning, brewhouse, storage cellar and residential buildings for the employees. Finally, in the fourth courtyard, you reached the machine house, the workshop, the distillery and the malt kiln. A curiosity of the brewery were two Indian water buffaloes that pulled a wagon that ran between the two locations Prager Strasse 20 (brewery) and 31 (cooperage). Carl Ferdinand had already used two such buffaloes in St. Marx. Just like the Hungarian oxen with the distant, twisted horns of the Dreher brewery, they were the trademark of St. Georg.

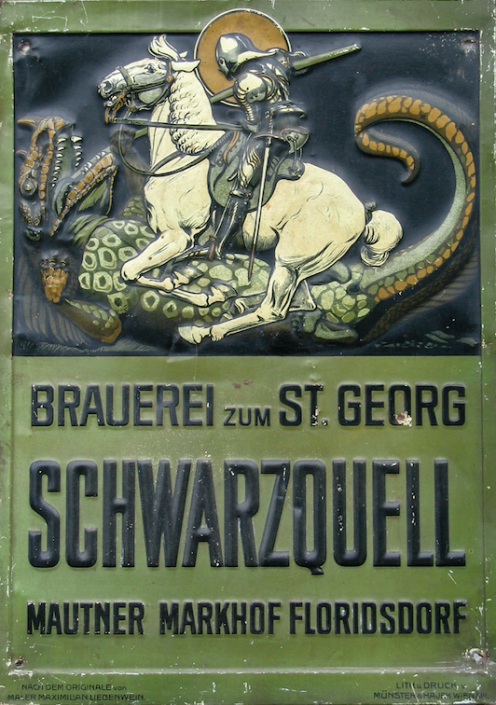

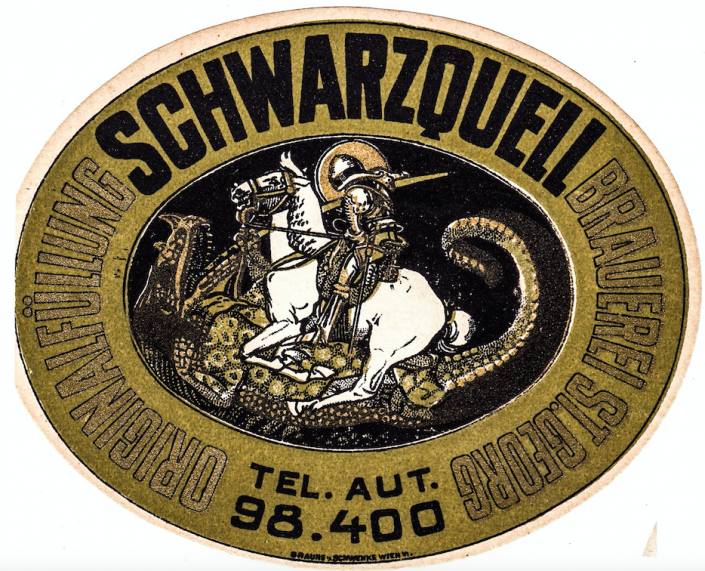

When Georg I Heinrich died in 1904, he left a company that was economically so extremely successful that his sons Theodor I and Georg II Anton, who took over the businesses in Floridsdorf and Simmering (yeast production, acquired from Victor in 1903), had to pay their siblings a total of 4 millions of crowns (equivalent to approximately 17.5 million euros) as an inheritance (in ten equal annual installments). Miraculously, the two sons managed to survive the extremely critical years that followed. Not only did the installments have to be raised, there was a price war with Gösser and World War I also had left its mark. The brewing industry fought a gigantic struggle for survival. People no longer had the financial means to afford quality, and the materials that were forced to be used for war purposes, especially copper, could not be replaced at the production facilities due to a lack of liquidity. There was a lack of raw materials, only hops were available. Millet, raw sugar, corn and later also sugar beet were used for brewing. Production fell from 200,000 hectolitres (1913) to 130,000 and in 1936 it was barely 60,000. After the war, the company fell into crisis. The alcohol factory had to be closed and the compressed yeast production relocated to Simmering. In 1926 40 civil servants and 270 workers were employed in the Floridsdorf factories. Instead of draft beer, only dark beer was brewed.

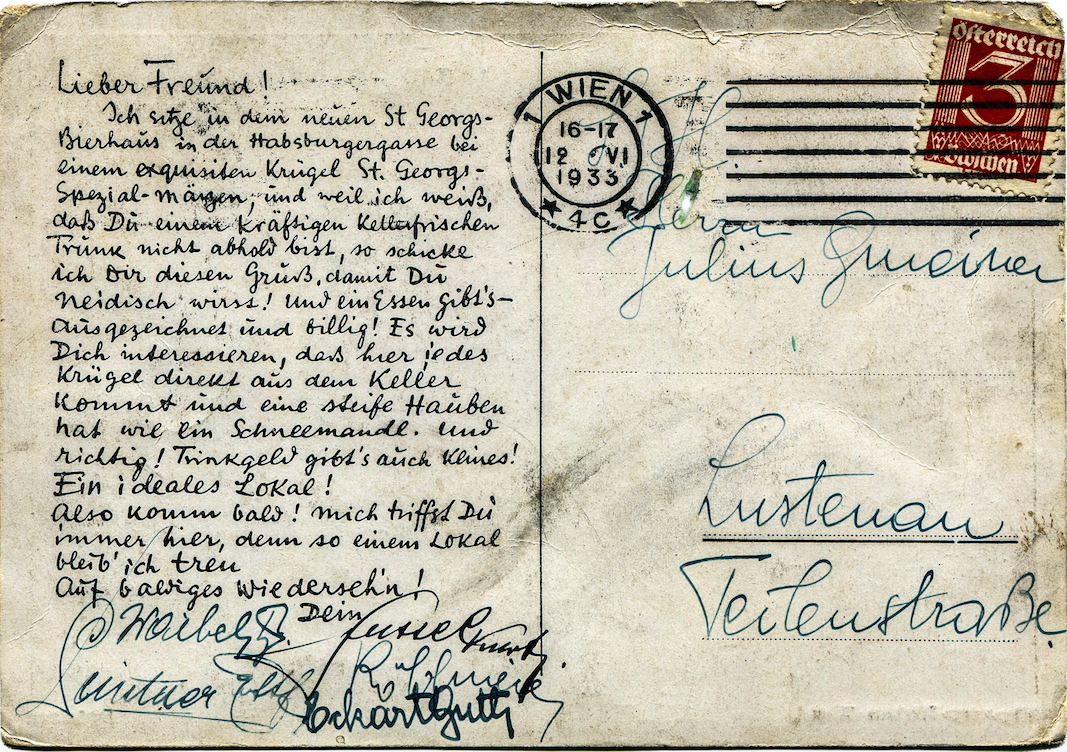

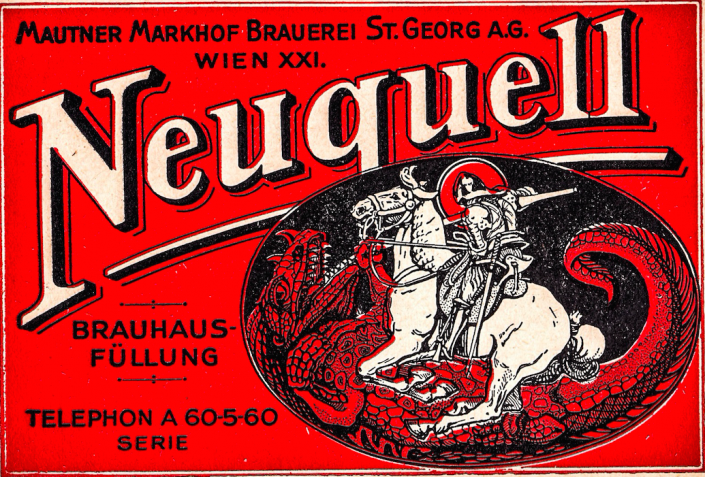

In 1930, the “St. Georg” was converted into a joint-stock company with the name “Mautner Markhof Brauerei St. Georg AG”, the share capital was 6 million old pre-war shillings (equivalent to approx. 14.5 million euros). Theodor was president of the board of directors, his brother Georg acted as vice president and their eldest sons Gerhard and Georg III became members of the Board of Directors. However, the financial situation was hopeless and the payment of a dividend could not even be considered in a single year. Austria was facing an economic abyss in the 1930s, unemployment had long since become unsustainable, tens of thousands of people did not receive any support whatsoever, which was equivalent to a death sentence. In 1934 political events did not stop at the brewery, either. Military was stationed and a cannon was positioned at the entrance, which was aimed at the “Hammerbrotwerke”. Georg II Anton died unexpectedly that year and Theodor withdrew from the business. The next generation then took over the management of the company and worked closely together.

Without Simmering, St. Georg as an independent company would have been forced to liquidate with a maximum liquidation proceeds of zero. Nevertheless, that brewery should still turn out as extremely profitable. In 1935, the family was able to take over the majority of the shares in the Schwechat Brewery. Unfortunately, St. Georg had to be shut down and closed at the same time, after only 43 years. The machines were dismantled and transported to Addis Ababa. The malting could not continue either because too little barley was allocated. All that remained was a beer depot, the ice cream factory and the printing shop.

During the Nazi era, the former St. Georg Brewery was home to the Jedlesee concentration camp and the headquarters of all the camps in the Vienna / Floridsdorf complex. A memorial stone in front of the district museum still reminds of this today. Although the area was badly damaged and largely destroyed at the end of Second World War, Manfred I brewed beer there again for a short time. In 1955 the remains of the building were removed, only part of the wall that surrounded the company premises still exists today. Until 1972, a lemonade factory and a large depot of the Schwechat brewery were housed on the site itself. Residential houses were built on the area on Prager Strasse.

Untrennbar verbunden mit der Brauerei ist das Mautner Schlössl, der ehemalige, bis heute als Bezirksmuseum erhaltene, Familiensitz.