The brewery was founded in 1632 under the name of Brauerei Klein-Schwechat on the Frauenfeld (Brauhausstraße 6) by Peter Descrolier, a former valet and chamber paymaster of the Habsburg Archduke Matthias. This was followed by other owners:

from 1634 Matthias and Anna Susanna Katherina Descrolier

from 1644 Konrad Krafft

from 1653 Sophia Krafft and Georg Puechner

from 1666 Dr. Georg Fockhy (relative of Daniel Fockhy/Mayor of Vienna)

from 1668 Baron Don Juan de Areyzaga (former Commander of the Cürassier-Regiment Des Fours)

from 1676 Baron Johann Jakob de Areyzaga

from 1685 Matthias Ignatius Nipho (member of the Empire Councellors, until 1694 owner of the land on which the Esterházypark/Vienna is located today)

from 1690 Raimund Sebastian Zaglauer von Zahlheim (father of Johann Adam von Zahlheim, Mayor of Vienna)

from 1730 Ernst and Franz-Josef Zaglauer von Zahlheim

from 1763 Heinrich Kajetan Graf von Blümegen (Chancellor of the Dukedom of Austria, Landlord of Erlaa)

from 1789 Franz Heinrich Graf von Blümegen (lived, like his father Heinrich Kajetan, the Chateau Altkettenhof in Schwechat; Blümelgasse, later Kochgasse, in Vienna´s 8th district was named after him)

In 1796 the brewery was taken over by Franz Anton Dreher, who in 1760 had come to Vienna with the so called Great Swabian Trek. He initially worked from 1773 as a beer waiter in a small brewery in Oberlanzendorf and from 1782 in the brewery “Im unteren Wird“/ Vienna Leopoldstadt. In 1804, at the age of 69, he married Katharina Widter, an 18-year-old master brewer’s daughter from Simmering, who gave birth to four children. Franz Anton died in 1820, the brewery initially went to his wife and

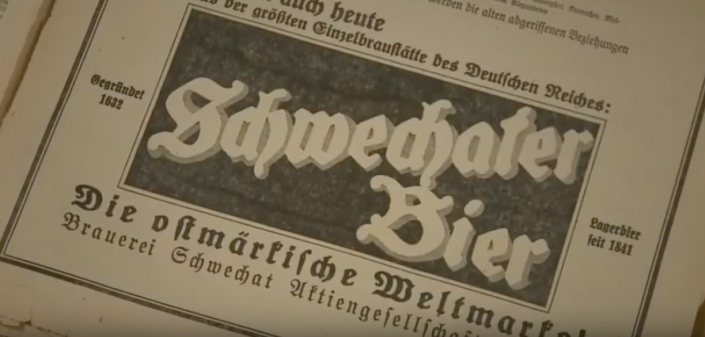

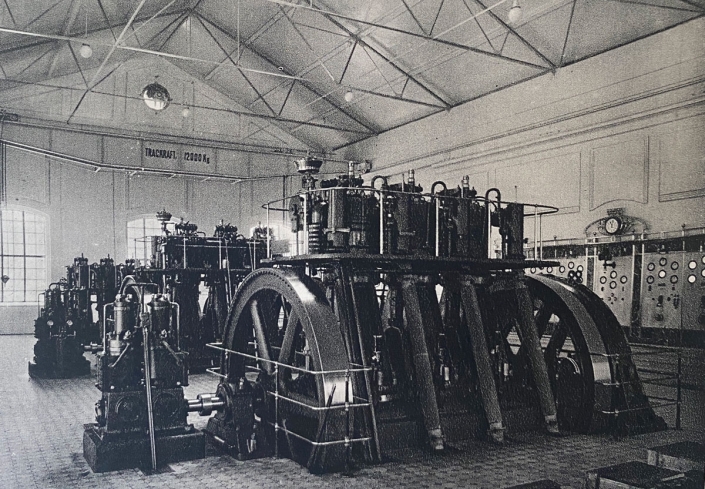

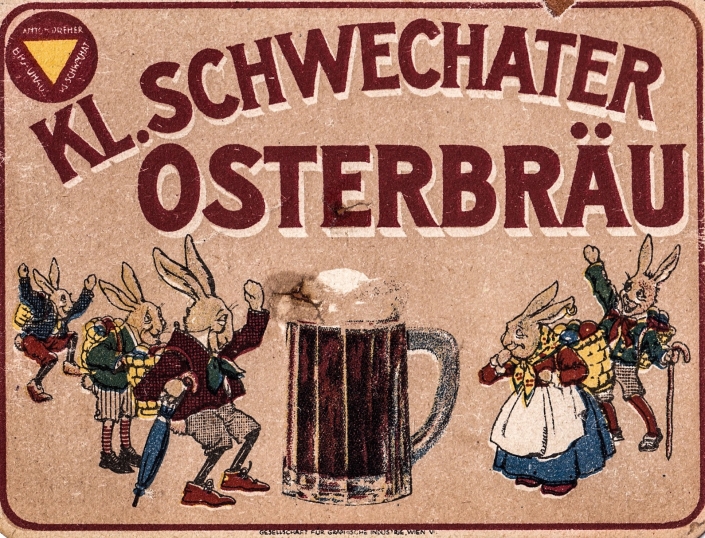

from 1839 to his son Anton Dreher (the elder), who invented the bottom-fermented Pale Lager in 1841, for the production of which he built huge ice cellars. In 1848 he was the first brewer to use a steam engine, which can still be admired in the Vienna Technical Museum. Under his leadership, the brewery developed into the world’s largest one.

From 1863 after the sudden death of Anton Dreher, at his express request, the company was run by the three directors Franz Aich (commercial director), August Deiglmayr (brewing business) and Cajetan Felder (who had, shortly before Anton’s death, been appointed administrator and guardian of his son, who was 14 years old at the time). Although there was not always unanimity between the three gentlemen, the brewery once again experienced an enormous boom. From 1865, after the takeover of two more Schwechat breweries, the company operated under the name “Brauerei Groß- und Klein-Schwechat” and opened another Dreher brewery in Trieste in 1869. That one was sold in 1928 and closed in 1976, whereby the well-established Dreher brand name has survived on the market until today and belongs to the Heineken Group.

In 1870 Carl Anton Maria Dreher came of age on March 21 and took over the management himself from that day on. He married Katharina Meichl, the daughter of the master brewer of Simmering, and in 1872 acquired Chateau Altkettenhof. When the Anton Dreher export brewery was founded in Saaz in 1898 (closed in 1948), the Dreher breweries formed the world’s largest brewery group of a sole proprietorship.

In 1905 his sons Anton Eugen, Eugen and Theodor officially joined the company – consisting of the breweries Schwechat/Vienna, Trieste/Italy, Michelob/Bohemia and Steinbruch/Budapest – as general managers. It was transferred to “Anton Drehers Brauerei AG” (stock corporation) without the involvement of a bank and had a share capital of 28 million kronen (around 140,000,000 million euros), which was divided into 560 registered shares of 50,000 kronen each. Therefore it was one of the largest public companies in Europe. The shareholders were exclusively family members, with Anton Dreher junior as president of the company holding 91 % of the voting rights. He appointed his youngest son, Eugen, as Vice President.

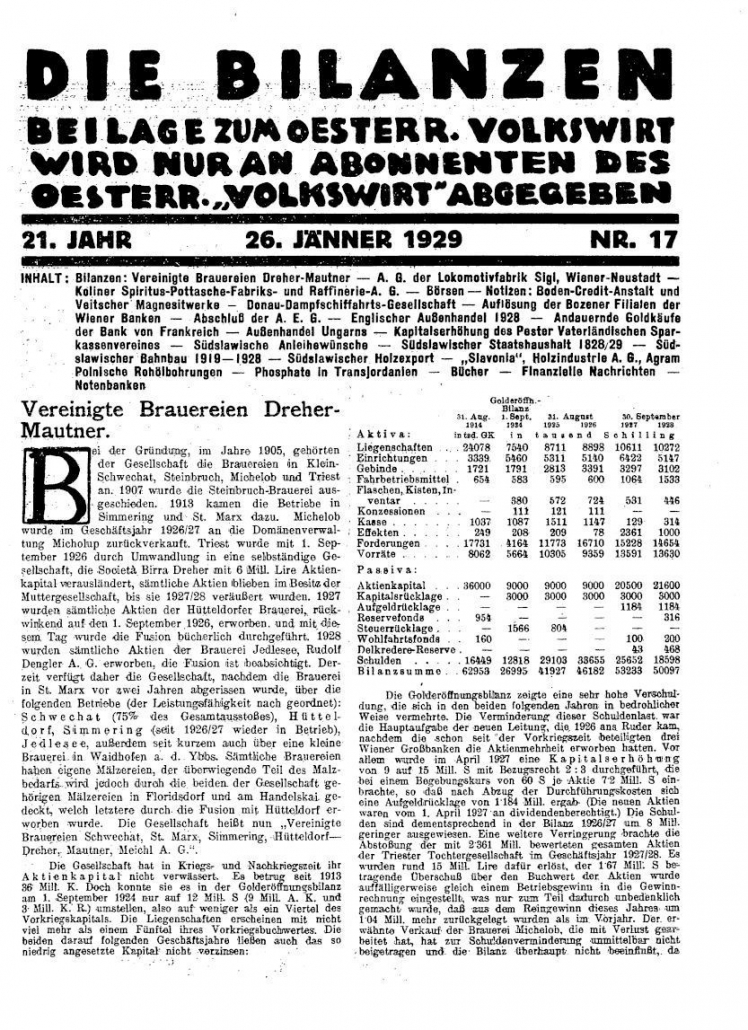

1913 – the legendary merger with the Ad. Ign. Mautner Ritter von Markhof & Sohn Brauerei St. Marx AG

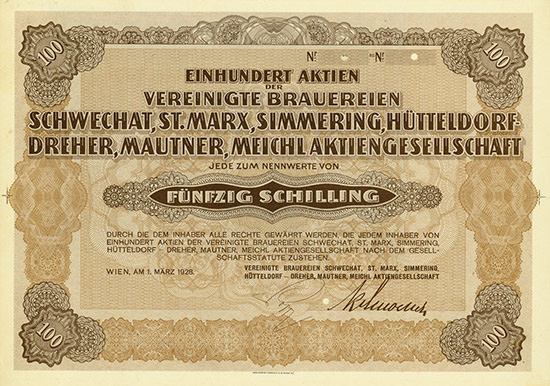

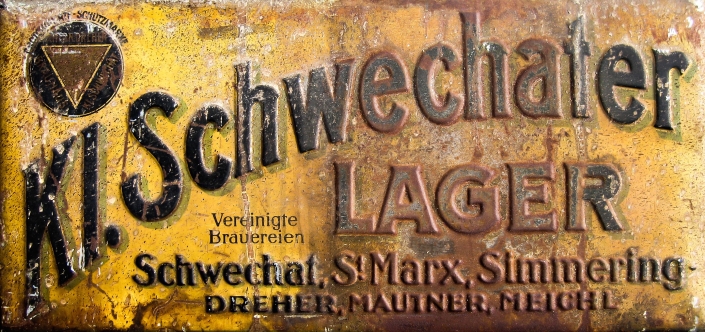

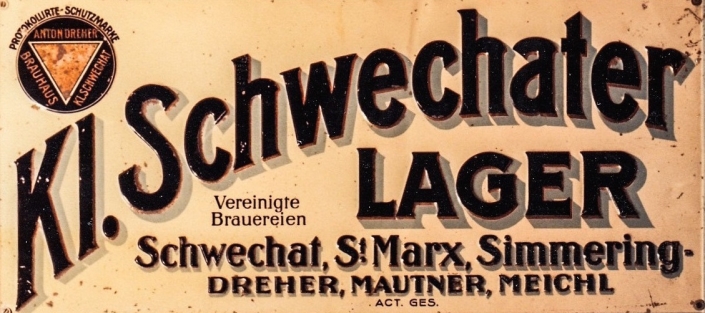

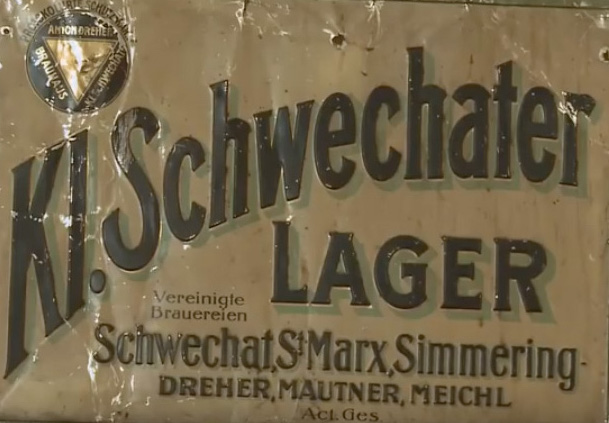

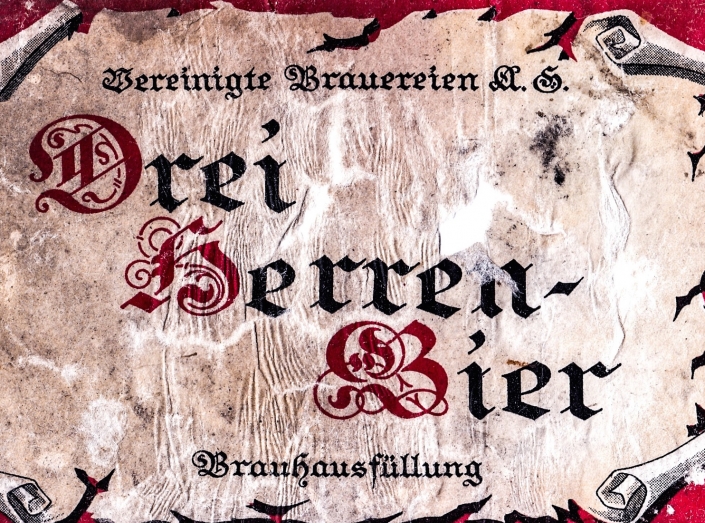

In 1913 the legendary merger with the “Ad. Ign. Mautner Ritter von Markhof & Sohn, Brauerei St. Marx AG”, and the “Brauerei Simmering Th. & G. Meichl AG” took place, which led to the foundation of the “Vereinigte Brauereien Schwechat, St. Marx, Simmering – Dreher, Mautner, Meichl Aktiengesellschaft”.

This merger had two main purposes: On the one hand, to obtain fresh capital for investments and, on the other hand, to facilitate the participation of family members in the company. Up until then, St. Marx was headed by Victor Mautner Markhof, and Simmering by Dreher’s brother-in-law Georg II Meichl. The ratio on the board of directors was set at 6: 4: 2 between the three men (Dreher around 60 %, Mautner Markhof around 30 %, Meichl around 10 %). Anton became president, Victor (after his death Kuno) and Georg vice presidents.

That public limited company was now one of the largest in the monarchy and the change of corporate was managed by three major Austrian banks: The Creditanstalt, the Viennese Bankverein and the Lower Austrian Escompte-Gesellschaft. The capital was 36 million kronen, the shares were not traded on the stock exchange, the seat of the stock corporation was relocated from Schwechat to Vienna in the Dreher-Hof on Landstrasser Hauptstrasse 97.

The 180,000 registered shares at 200 kronen remained largely in the possession of the members of the three families until Anton’s death, but small shares had to be assigned to the banking consortium. Victor Mautner Markhof received shares to the value of 10 million kronen, Georg Meichl to the value of 5 million kronen. The Creditanstalt, the Viennese Bankverein and the Lower Austrian Escompte-Gesellschaft won one million kronen each and a board member mandate. The first board of directors of the United Breweries also had three bank directors: Kux from the Lower Austrian Escompte-Gesellschaft, Popper Artberg from the Viennese Bankverein and Hammerschlag from the Creditanstalt. That was common practice with large stock corporations to document the connection with leading banking institutions. Pure family businesses were a thing of the past. In the monarchy the market share of the United Brewery with around 3000 employees was 35 %. With the exception of Ottakring, Liesing and the Municipal Brewery, all other Viennese breweries fell victim to their aggressive fierce competition in the following years.

The First World War, which among other things resulted in the fact that no barley was available at all, hit the brewing industry extremely hard. Also due to the war, Schwechat was in a technically outdated and poor condition due to the loss of copper equipment. The production output of the United Breweries in 1916/17 was 94,000 hectolitres, would you believe it. In comparison, the brewing period 1911/12: Schwechat 470,000 hectolitres, St. Marx 480,000 hectolitres. Not until 1923 was it possible to brew a “peace beer” again, despite the raw material-related restrictions of the post-war period.

Instead of renovating, Alfons Erhard – who had managed the Schwechater Brewery very commendably from 1887, but was no longer able to cope with the changed conditions – tried to persuade as many innkeepers as possible in the federal states to purchase his beer by offering a low purchase price. In return, he offered them the rescheduling of their high bank debts and gave them loans, which were also granted by the investment consortium without asking too much. Soon, however, this expansion into the federal states turned out to be largely inefficient and unprofitable, also due to the expensive transport costs. Although that policy led to a new production record of more than one million hectolitres between 1924 and 1926, the debt level rose enormously at the same time: from 12 to 33 million schillings, which were only partially offset by dubious claims of 27 million schillings from the landlords mentioned (one schilling of that time corresponds to today’s 3.7 euros). The financial collapse threatened and no profit could be made and no dividends could be paid out. Erhard had a considerable part in the decline of the United Breweries during that period.

1926 – the end of the Dreher era

As long as Anton Dreher jr. was President of the United Breweries, the banking consortium had little influence on the business. When he died in 1921 and Bernhard Popper Artberg, General Director of the “Bankverein”, wanted to claim the presidency, the brewing families were still strong enough to be able to agree on Anton Eugen, who, although without much influence, but with a strong majority of shares and his General Director Alfons Erhard, headed the company. Fundamentally, the situation only changed in 1925, when also Anton III died and the end of the Dreher family in the Schwechat Brewery was soon to follow. Theodor had already died in a car accident in April 1914 and Anton Eugen’s son, Anton IV, had died in the First World War in 1917. Finally, Oskar, the 11-year-old son of Theodor and last male representative of the Viennese line, died in 1926. The logical successor as president would have been Eugen Dreher, but he was aware of the increasing economic problems and he had no desire for further burdens besides his Hungarian companies. Bernhard Popper Artberg took his chance and made him an offer that gave Eugen a lot of capital to expand his Hungarian industrial empire, even though it was basically bad. His 70,000 shares were transferred to the banking consortium (“Niederösterreichische Escomptegesellschaft, Bankverein”, “Creditanstalt” and “Bodencreditanstalt”), each at a price of 66 schillings (approximately 244 euros), with a further option for the remaining 40,000 shares from Anton III’s estate. So, it came about that the theoretical share value of the 60 % stake held by the Dreher family was only 7.2 million schillings (approximately 26.6 million euros). In 1913, it was still 22 million crowns (approximately 81.4 million euros), with the crown of that year having around 30 % more purchasing power than the shilling of 1926. From Eugen’s point of view, he had left a sinking ship that he could just about sell for a profit. The 130-year association of the Austrian Dreher family with the Schwechater Brewery definitely ended when in 1926 Alfons Erhard, the long-standing general director and last guardian of the “Dreher tradition”, died of a stroke.

Victor Mautner Markhof’s widow, Helene, also died in the fateful year of 1926. Contrary to his recommendation to sell her shares to Dreher, however, she had kept his 30 % stake, which was very wise, since the money she would have received for the sale would have been quickly devalued by the beginning of the inflation. After her death, Victor´s four surviving sisters inherited that big stake, which they only wanted to sell quickly. Neither the Floridsdorf relatives nor the Meichl family had the money to buy those shares, and they were hardly interested in it. Georg II Anton and Theodor I, who were in charge, just reorganized their enterprise, which in addition to beer in their St Georg`s Brewery increasingly also produced fruit juices, mustard, vinegar and spirits. Bernhard Popper Artberg became active again and also succeeded in acquiring the shares from Victor’s inheritance at a “shamefully low” price (in 1935 only Kunos widow owned a very small block of shares). Within a short time, the bank consortium had gained the majority of shares in the United Breweries AG for relatively little money.

The share capital of the United Breweries, which – due to the gold balance law – then amounted to 9 million schillings (approximately 33.3 million euros), rose to 15 million (approximately 55.5 million euros) through a capital increase. It was divided into 300,000 pieces of 50 shillings each. Once again, the brewing families were able to defend themselves against the complete takeover of the management of the board of directors by the banks, which were already majority shareholders: No president was elected, Kuno Mautner Markhof and Georg III Meichl led the company as vice-presidents, with Kuno also temporarily acting as general director. Rationalization measures and debt reduction began immediately, and extensive commercial and technical reforms in those years laid the foundation for a new, healthy upward trend of the enterprise.

In addition to the St. Marx Brewery, which had already been closed during the war in 1916, the three Dreher branch breweries that were foreign in the meantime, were also no longer part of the United Breweries. Steinbruch was converted into an independent “AG” as early as in 1916, which, however, remained in the family due to the change of citizenship of Eugen Dreher and which he managed very successfully until 1949. Under pressure from the Italian state, Trieste was converted into its own “AG” in 1926 and sold shortly afterwards. In the same year, the brewery in Michelob was spun off and acquired from Kitty Wünschek, the daughter of Anton III, who closed it in 1928.

1927 – bankers instead of brewers

The next bang followed in 1927. The bank consortium and the industrialist Richard Schoeller, who owned the majority of shares in the “Hütteldorfer Bierbrauerei Aktiengesellschaft”, agreed to merge their breweries and to add the word “Hütteldorf” to the company name. The Hütteldorf Brewery, owned by the Schoeller, Gomperz and Wirth families, was managed by Konrad Schneeberger. After the merger, Schneeberger took over the management of the company as “primus inter pares” of a triumvirate consisting of himself, Kuno Mautner Markhof and Georg Meichl. Within a very short time until his death in April 1936, he was the unconditional ruler supported by the trust of the major shareholders, even during the time when the Mautner Markhof family held the majority of the shares. With an iron fist and energy, he managed to reduce the enormous amount of almost 39 million schillings (approximately 144.3 million euros) in debt capital on August 31, 1926 within nine years – while beer production fell from 1,150,000 to 400,000 hectolitres at the same time – to 4.2 million schillings (approximately 15.5 million euros) on September 30, 1935 and practically made the debit interest balance 1925/26 of 51 million schillings (approximately 188.7 million euros) disappear. The share capital was reduced to 20 million schillings (approximately 74 million euros) through the purchase of a nominal 1.6 million schilling (approximately 5.9 million euros) of own shares. At the same time Schwechat was really generously and modernly expanded and modernized by an investment of 1.2 million schillings (approximately 4.4 million euros) in just three years.

Meanwhile, under the management of Georg Meichl, part of the brewing activities were relocated to the Simmeringer brewery, which already had been partly closed in 1917 and was finally closed in 1930 after the Schwechat renovation was completed.

Among other steps to reduce transport costs, the delivery of Schwechater beer was limited to Vienna, Lower Austria and the northern Burgenland. An example shows a contract with “Brau AG”, according to which the Viennese “Grand Hotel” should only offer Linz Poschacher beer and in Linz the hotel “Zur Kanone” only offer Schwechater beer. All other Viennese and Upper Austrian restaurants should only serve regional beer. DDr. George III Mautner Markhof stated in his lecture on June 5, 1974, “Looking back, I would like to say that it is only thanks to Schneeberger’s policy that we were later able to acquire the majority of Schwechat”. It was also thanks to him that a dividend of 10 % could be paid out for the first time in 1927.

After those changes, the bank consortium with a share of 79 % had finally taken power and Bernhard Popper Artberg was finally able to take over the presidency in 1927. With him came a man who had no relation to beer at all. His vice-presidents were then Paul Hammerschlag, Richard Schoeller (who remained a major shareholder until his death in 1950), Wilhelm Kux (as a representative of the Lower Austrian “Eskompte-Gesellschaft”) and, with a small share, Georg Meichl (as the last representative of the brewers). Since the “St. Marx Group” had four seats, Kuno was still a member of the board of directors until his death in 1930, as were Victor’s brothers-in-law Karl Dittl von Wehrberg and Ernst Freiherr von Haynau.

Popper Artberg and Schneeberger worked according to the principle of “modernization and rationalization, maximum economy and operational reliability while maintaining quality”. The market value of the shares, the nominal value of which was 50 schillings (approximately 185 euros), reached market values of almost 90 schillings (approximately 333 euros) in 1929. Needless to say, that, of course, left many workers behind.

“But it is very strange and regrettable that the typical Schwechat beer has completely disappeared. When people talked about the Viennese lager, that was actually just the Schwechater beer, as the other breweries, as already mentioned, either did not produce that beer at all or only produced a very small quantity of it. The Schwechater lager, or the Viennese lager, which was very much reviled by some for its colour, was, as far as I can remember the quality of it, a very excellent drink, full of taste, splendid foam, well stored. […] Now the name ‘Schwechater Lager’ stands for a completely different beer, a completely different type of beer and entire generations of Drehers would have turned in their graves.” “The brewing and malting industry” by Eduard Jalowetz, published in 1928. It should take another 90 years before Dreher’s lager celebrated a resurrection in the winter of 2015/2016.

1930 – Great Depression

Nothing would have stood in the way of a further positive future for the brewery if the world economic crisis in 1930 had not brought all economic hopes to an abrupt end. That crisis primarily affected the owners, thus the three banks that, ready for bankruptcy, merged in 1934 with a support action by the state to form the largest Austrian bank, the “Creditanstalt-Bankverein”. They continued to be the majority owners of the United Breweries, while “Industriekredit AG”, which managed the former holdings of the Lower Austrian “Eskompte-Gesellschaft”, held a minor share. The “CA-BV” board member Alfred Heinsheimer remained president of the brewery’s board of directors until his death in 1935.

The 150-year-old brewery in Jedlesee, which had also been a stock corporation since 1922, was merged. After a share swap, it was shut down in 1930 and its main shareholder, Wolfgang Bosch, was given a seat on the board of the United Breweries in addition to a share package. He was the last descendant of another dynasty of brewers who had been, together with the related Dengler family, active in Jedlesee for more than 100 years. Through the acquisition of the two breweries the share capital was increased to 21.6 million schillings (approximately 80 million euros). It should also be mentioned that the small brewery in Waidhofen an der Thaya was also merged, its president Paul Hammerschlag already had a seat on the board of directors at that time.

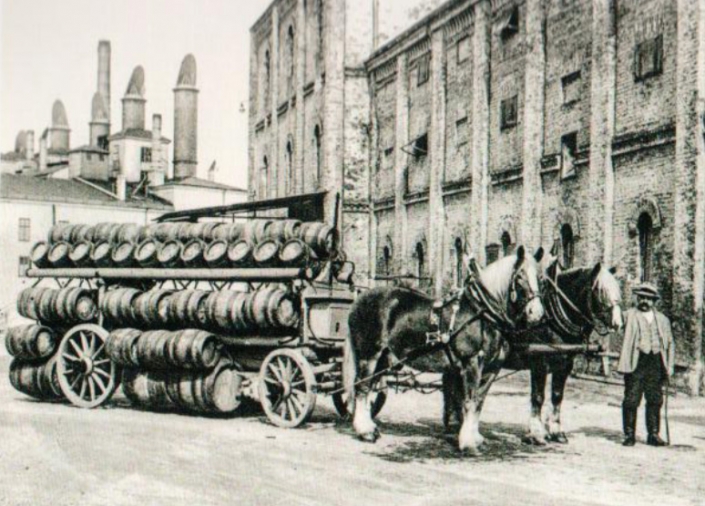

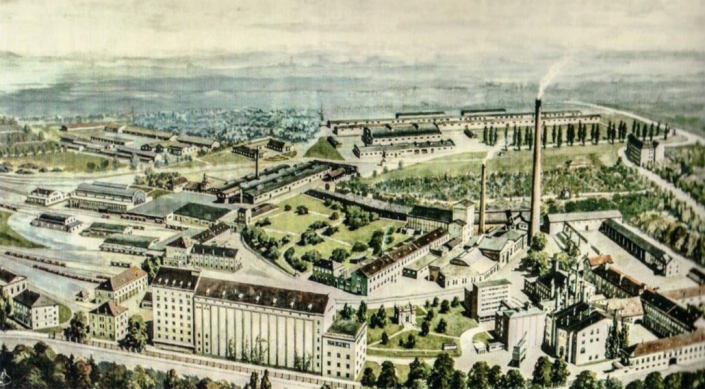

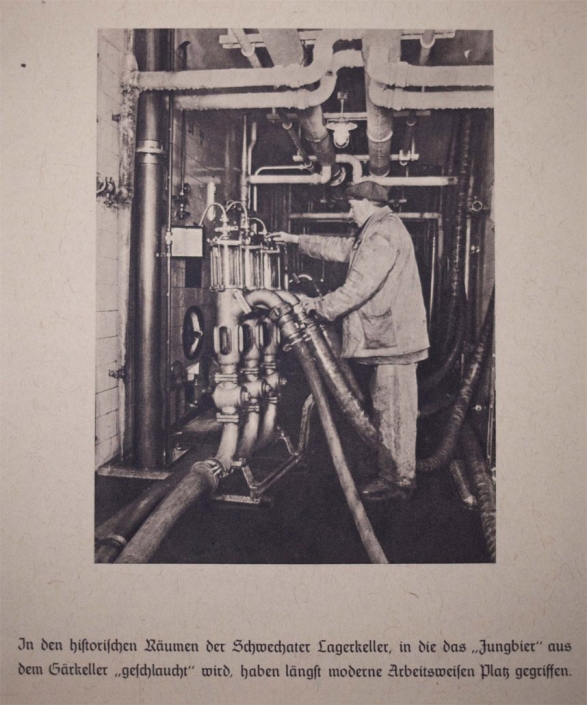

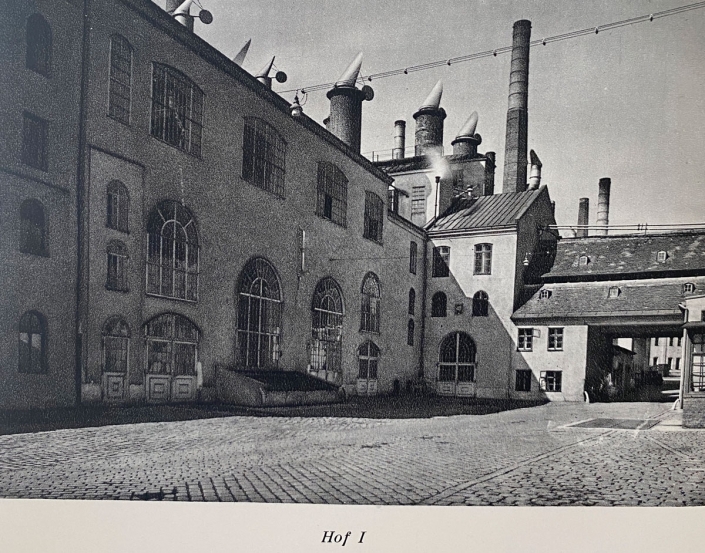

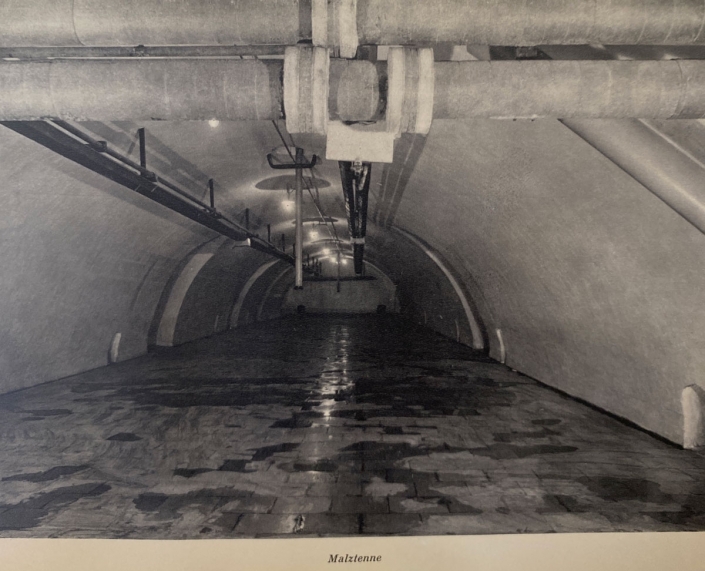

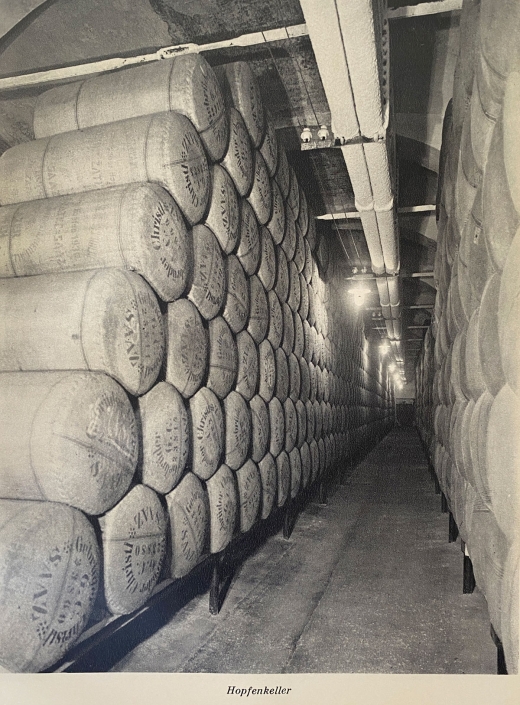

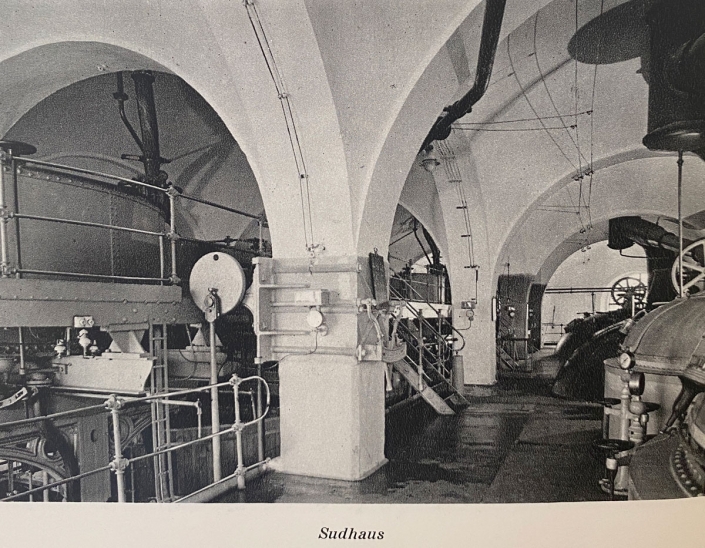

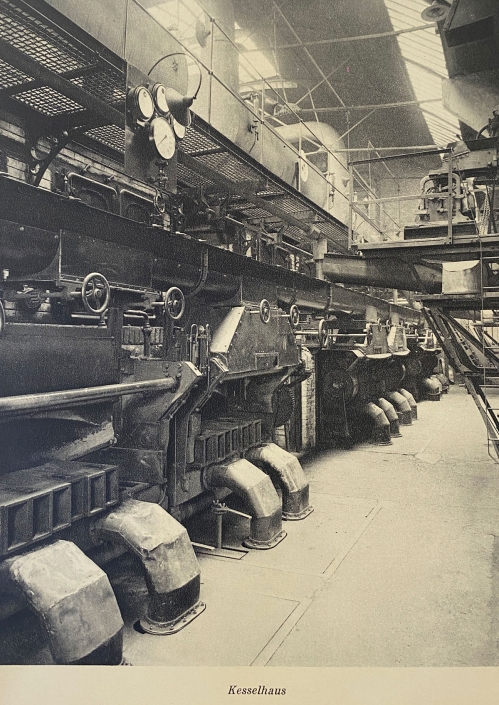

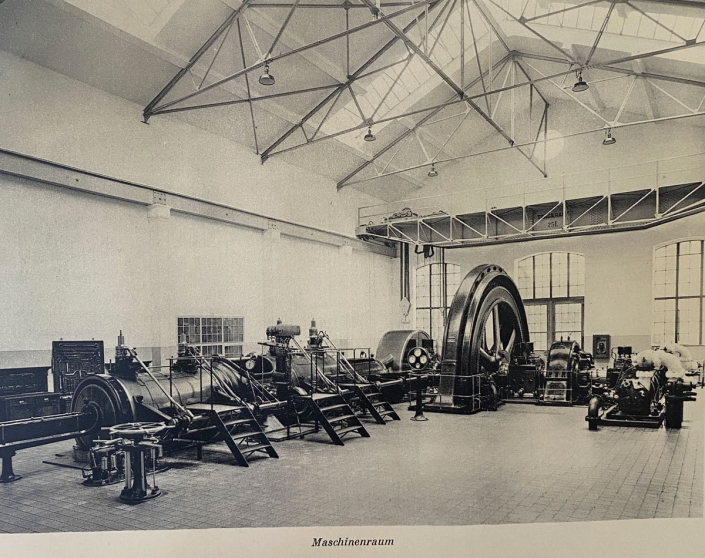

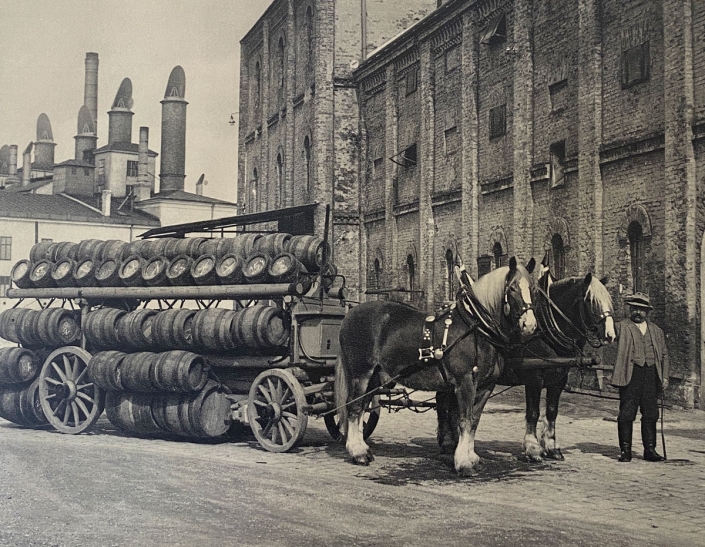

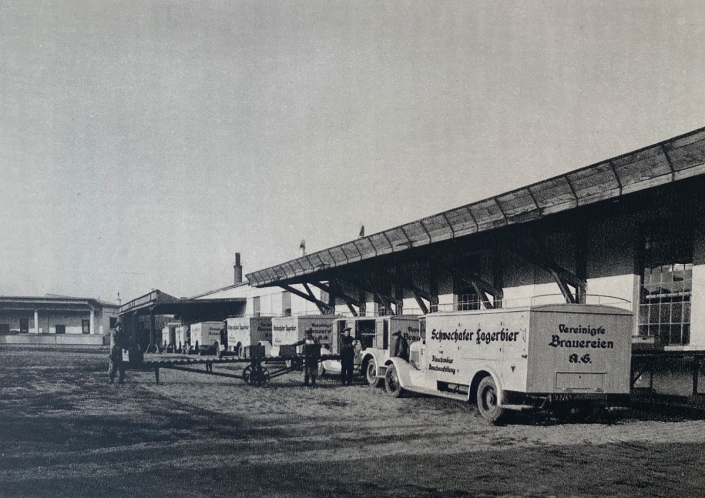

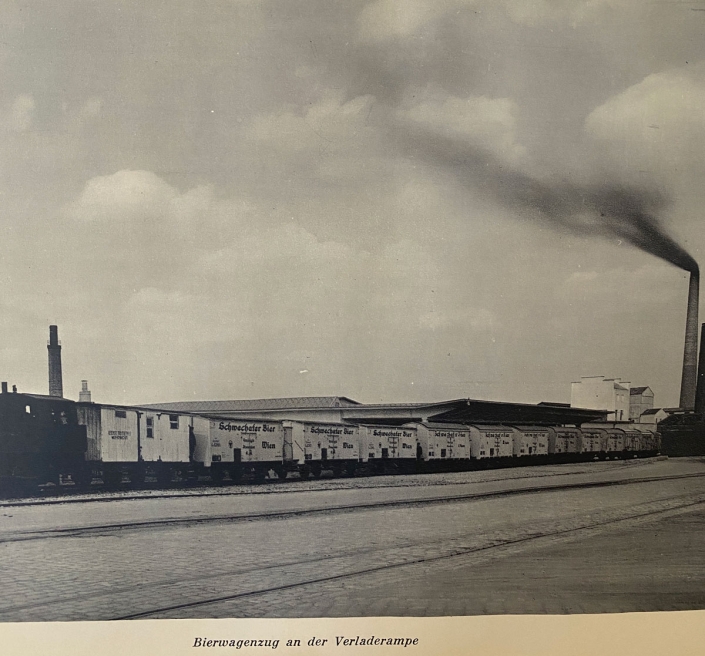

To everyone’s regret, the Hütteldorfer Brewery also had to close in 1932 due to the decline in beer consumption during the economic crisis. Schwechat was then the only brewery of the stock corporation and produced an annual output of around 800,000 hectolitres on 363,000 m2 of operating space. About 1000 workers were employed, the machine had 3000 HP and a storage room of 350,000 hectolitres, which was cooled by ammonia compressors with an hourly output of 1,500,000 calories and a network of cooling pipes 90 kilometers in length. About 1000 workers were employed, the machine had 3000 HP and a storage room of 350,000 hectoliters, which was cooled by ammonia compressors with an hourly output of 1,500,000 calories and a network of cooling pipes 90 kilometres in length. In the three-storey-deep basement there were a total of 342 concrete tanks, each holding 450 to 600 hectolitres. The system was a showcase of warehouse technology and the largest of its kind in Europe. Open fermentation vats disappeared for good, but stainless steel tanks did not gain acceptance until after 1945. In addition to the works railway with 50 freight wagons, there were then 200 trucks and only 100 horses. In addition to the in-house one in Klein-Schwechat, there were only the two malt houses in Floridsdorf and on Handelskai as well as 92 different real estates such as beer halls, beer depots and residential buildings. The funds required for renovations and new investments in the double-digit millions could all be raised from profits.

Konrad Schneeberger had to go through a difficult time during the last years of his life. The fact that in the early 1930s the Schwechater Brewery supplied half capacity to a sales market for which all capacities of it and the merged breweries in St. Marx, Simmering, Hütteldorf and Jedlesee were needed before 1914, illustrates the drastic decline in beer consumption during that period. The brewery’s output fell from 833,000 to 380,000 hectolitres by 1936. Investment activity was almost completely stopped, the dividend was gradually reduced from 12 % to 2 % between 1928 and 1933 and cancelled altogether in 1934. An attempt was made to reduce the losses through the production of ice cream, non-alcoholic and low-alcohol beverages, and a subsidiary was founded on the Simmeringer brewery grounds, which was later joined by an operation on the grounds of the abandoned St. Georg`s Brewery. From today’s perspective, however, that expansion of the company was only carried out half-heartedly, as the subsequent boom in the soft drinks market had not yet been foreseen. Even the attempt to produce a practically alcohol-free light beer with the name SOMA was hardly successful.

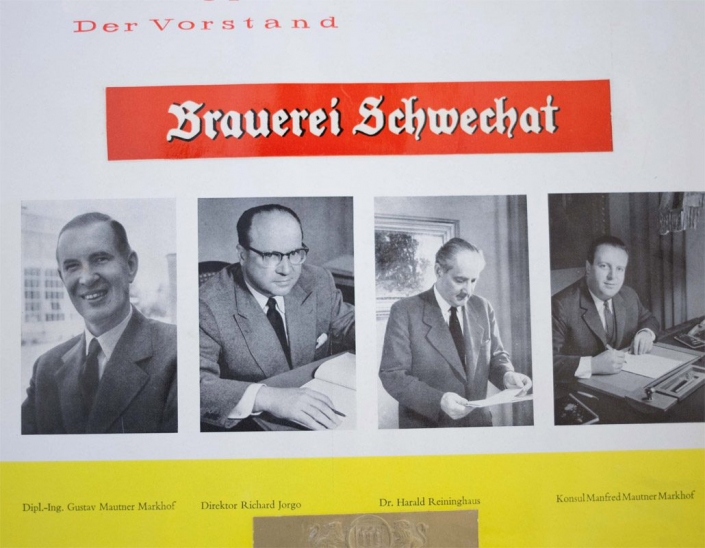

1935 – Georg III Buwa acquires the majority of the Schwechat Brewery for the Mautner Markhof family

In 1935 the debt level was almost completely eliminated and the rationalization was completed. The “Creditanstalt-Bankverein” and “Industriekredit AG” owned 60 % and the Mautner Markhof family and their friends Richard Schoeller, Georg Gomperz and Georg Meichl owned 30 % of the 400,000 shares. 10 % were free float. The brewery was not listed on the stock exchange, so there was no price for the shares on the securities market. After the death of Georg II Anton and the retirement of Theodor I due to old age, their sons, Georg III, Gustav I, Manfred I, and Gerhard, took over the management of the business. Among other things, George III was President of the Association of the Food and Beverage Industry, President of the Spirit, Yeast and Brewing Industry, the Vienna Chamber of Commerce and the Lower Austrian Trade Association, Vice President of the Federation of Industry during those years, and from 1934 to 1936 Federal Economic Councillor and from 1936 to 1938 State Councillor, which corresponded to a member of the National Council during the times of the Corporate State.

Georg III in a lecture on June 5, 1974 about the year 1935, “It was around that time that I had the idea of trying to acquire the majority of the United Breweries. Although the chances seemed extremely slim, I wanted to give it a try. My wishes could be fulfilled because the Dutch general director of the “Creditanstalt-Bankverein”, Adrianus van Hengel, who was appointed by the foreign creditors, basically pursued the policy of reducing the enormous industrial holdings of the institute he directed.” A suitable intermediary was found in Ludwig Draxler, who was promised a success bonus of 200,000 schillings (today 740,000 euros). Draxler was the lead attorney of the “Heimwehr” and shortly after that contact also became finance minister of the Corporate State, which, of course, greatly benefited the project. He brought van Hengel to the point where he was ready to sell the 30 % stake at a price of 35 schillings (approximately 130 euros). At the same time, the “Industriekredit AG” was ready to sell its 28 % stake at the same rate. “That was the first step”, he said at the time, “But where do you get the money from?” For the time being, he had to be content with buying the shares of the “Creditanstalt-Bankverein”. 35 schillings corresponded to 70 % of the issue price and to 40 % of the 1929 price, but considering the economic situation, it was also called appropriate by Schneeberger.

The buyer of the shares was the St. Georg Brewery – thus the “Floridsdorfer Mautner Markhofs” became the main shareholders of the Schwechat Brewery. There, in the truest sense of the word, the last reserves were scraped together by selling all other investments, liquidating all reserves and taking out corresponding corporate loans. On the one hand, to acquire the largest single package, the 28 % stake of the “Industriekredit AG” in the Schwechat Brewery, and on the other hand, to buy further shares in order to obtain a majority from other shareholders. In a second step, in order to secure the necessary liquidity for St. Georg for the cancellation of those loans, the entire fixed assets of St. Georg were acquired from the brewery in Schwechat. A total of 232,000 shares changed from the banking consortium to the Mautner Markhof Group for 10.4 million schillings (approximately 38.5 million euros). St. Georg had become the main shareholder of the Schwechat Brewery. The acquisition was completed in 1936, the brewing activity in St. Georg was stopped, later on, the buildings were used as a malt house and for the production of non-alcoholic beverages.

As early as in 1935, after the death of Alfred Heinsheimer, Georg III was elected Chairman of the Board of Directors and completely changed its formation. The bank representatives had to resign and made room for relatives and all the families they were friends with. Georg Meichl and Richard Schoeller remained Vice Presidents. The economic crisis at that time with its mass unemployment had reached its climax, and so both workers and employees welcomed the change of ownership from anonymous investors to the Mautner Markhof family, whose reputation as an employer had already enjoyed a very good reputation for generations. Despite the further decline in sales, the new owners were even able to distribute a dividend of 5 % between 1935 and 1937, which is all the more remarkable since production had reached its all-time low in 1936.

At the general assembly of December 1, 1936, at the suggestion of General Director Schneeberger, the company was named “Mautner Markhof Brauerei Schwechat AG” (that name was only allowed to exist for one and a half years and did not even make it onto a sign or a beer mat). A new period began under the leadership of the Mautner Markhof family, which was to last exactly 50 years.

1938 – The Schwechat Brewery in the times of National Socialism

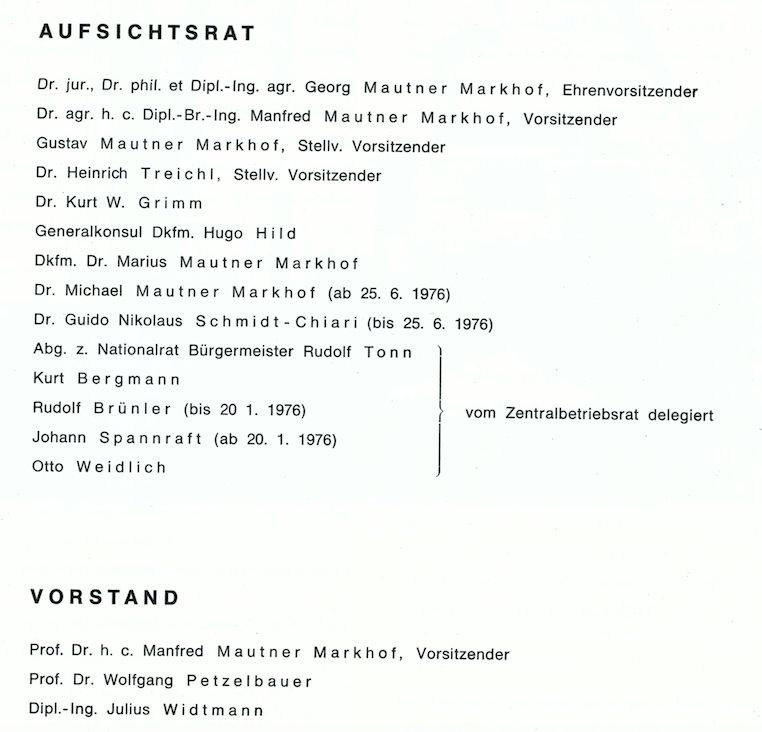

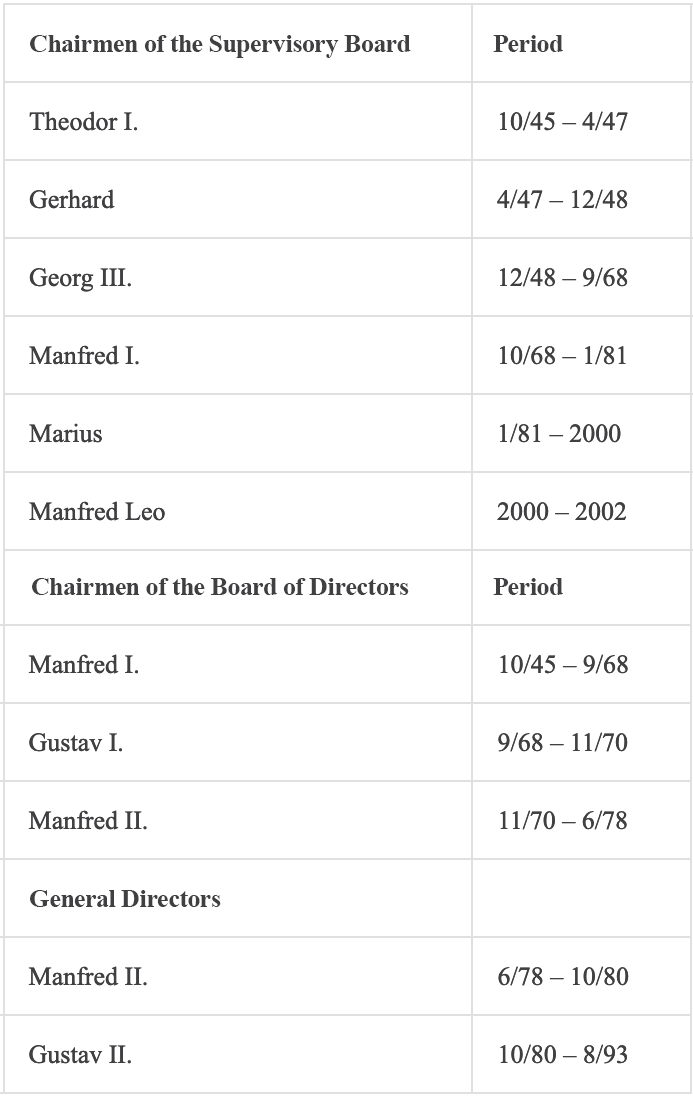

When Adolf Hitler and his army marched into Austria on March 12, 1938, that also had immediate and lasting consequences for the Schwechat Brewery. In September, the adjustment to the German stock corporation law was carried out and for the first time a supervisory board was appointed instead of a board of directors, led by Georg III. His deputies were still Georg Meichl and Richard Schoeller as well as Gerhard. Manfred I became chairman of the board and Gustav his deputy. As in many other Austrian companies, political changes took place in the brewery soon after the “Anschluss”. All gentlemen who were not “party-conform” had to resign from the supervisory board and the executive board and were replaced by mostly incompetent National Socialists who also interfered in the company management. Even before 1938, the second management level of the brewery had been riddled with unnoticed, then illegal Nazis who then sensed their chance for a career. Although Georg and Manfred succeeded in dismissing their ringleaders without notice, that was given very negative credit to both of them in the months that followed.

From an economic point of view, the first financial year after the reunification of Austria with the “German Reich” had such an impact that Schwechat, with more than a million hectolitres, had become the “largest single brewery of the German Reich”. Thus, emissions had almost tripled compared to 1937. At the beginning, the family was confident to be able to continue to operate economically under the new regime, so that, together with Gustav Harmer (partner in the joint pressed yeast factory), an attempt was made to buy the Ottakringer Brewery from the Jewish Kuffner family in April 1938. Harmer, who originally only wanted to take over the yeast production, had to acquire the entire Kuffner group on his own after a massive objection by the National Socialists against participation of the Mautner Markhof family.

Since the National Socialists did not want to leave the Schwechater Brewery in Austrian, but in purely so called Aryan hands, they made the first attempt in 1938 to bring the majority of the shares and thus the entire Austrian brewing industry under their control, in order to place it in “Reichsdeutsche” hands. The “NSDAP” was looking for reasons to get family members out of the way. Among other things, dismissals of party members, the attempt to take over the Ottakringer Brewery and the acquisition of the United Breweries – which were heavily criticized as “fraud on the national wealth” – were used. George III almost ended up in a concentration camp, but was able to prove that both, the low purchase price of the shares in the United Breweries and the relatively high takeover value of the St. Georg Brewery were based on reports from independent experts. As late as in December 1938 Georg III resigned as “President-General Director” of the new supervisory board formed according to German company law, as a protest. The family had to sell a four percent stake under pressure from the party, but that had no effect on their majority. The committees were newly appointed: Wolfgang Widter (related to the Dreher family, and who had been the secretary in the brewery for many years) became the new central director and formal company manager. He was just as loyal to the Mautner Markhof family as Karl Dittl-Wehrberg, who became chairman of the supervisory board after Georg’s resignation.

Both Georg and Manfred left Vienna after their Gestapo intermezzi to save their lives. Georg decided to go “abroad instead of concentration camps” and spent a few years in Potsdam, Spain, Switzerland and Italy. Georg III wrote in a curriculum in 1978, “Since I was convinced that the National Socialist regime was unquestionably over organized, I returned to Vienna after Baldur von Schirach’s appointment as “Gauleiter” and lived there unchallenged, but abstaining from any industrial activity whatsoever, as a private individual until the end of the war.” Manfred stayed in Berlin for months, from where he continued to run the enterprise in the background as deputy chairman of the supervisory board, and returned in May, 1940.

It could be thwarted that the majority of the shares had fallen into “Reichsdeutsche” hands but the family name had to be eliminated from the company name in 1939. The new name “Brauerei Schwechat Aktiengesellschaft”, however, did not only survive- the end of the war, but also remained unchanged for decades.

After 1939, the Second World War hit the brewery hard. By September 1940, a quarter of the brewery workers had gone to war, women and, above all, increasingly foreign workers were employed for the hard work. Up until the very end, Bürckel’s successor, Gauleiter Baldur von Schirach, tried to activate the last reserves of capable brewery workers, so that in February 1945 the workforce no longer even comprised half of 1939. Members of the family were also drafted into military service. We know from Gustav I that he was an armoured infantryman until he joined “IG Farben” as a civilian after suffering from severe jaundice. Manfred had to serve as a motor vehicle driver for a year and a half with the anti aircraft and only barely escaped a war mission on the Eastern Front thanks to his wife Maria “Pussy” who pulled strings to declare him as indispensable at the yeast factory. His son Manfred II experienced the war as an air force helper in several “Wehrmacht” units and was even held in US custody for a few days in Regensburg, from which he fortunately was released very quickly. Gerhard’s son Heinrich was conscripted towards the end of the war and wounded three times at the front.

Since one wanted to increase the capacity through investment in the first years of the war, an application by Manfred I was approved in September 1938 for a 25 % capital investment grant for the construction of a new barley silo and a malt house and the two facilities could be put into operation in 1942. When “100 years of lager beer” was celebrated in 1941, problems arose immediately, as Anton Dreher was not recognized as the inventor. General Director Widter stated in a board meeting, “The newspaper advertisements, which referred to our former position as an export brewery in connection with the introduction of lager beer in our “Schwechater Brewery” 100 years ago, were the subject of attacks from the “Altreich”, which prompted us to further research the historical background of our claims made in the advertisements. This research has now clearly shown that the world’s first pale lager originated from the Schwechat Brewery in 1841. This fact, which is important to us, will be recorded in a corporate magazine that will be published soon in order to re-establish the reputation of the Schwechat Brewery.”

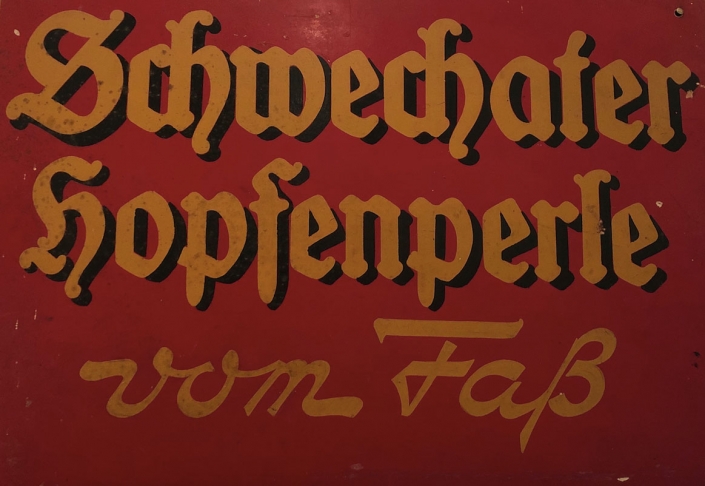

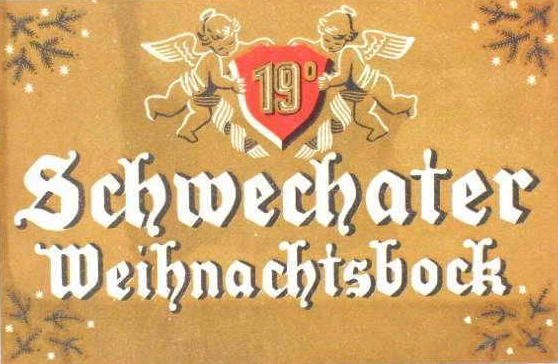

In the Second World War, there was a much better raw material planning than in the First World War, so production was still more than a million hectolitres until 1943. However, from December 1939 on only 9-degree beer was produced and from May 1940 on also 6-degree beer, although the better could only be delivered to institutions of the party until the last days of the war. A 10- degree special “Hopfenperle” beer was also brewed from October 1940 onwards, but it was not available for sale but only available for special occasions. “SOMA”, a beer-like malt drink, and other lemonades were also produced. From 1941 the delivery quotas for bottled beer and from 1944 also those for draft beer were limited. At the end of 1943 large parts of the brewery cellars for war-important operations were occupied and in 1944 with the start of the air raids on Vienna, just 25 % of the beer volume of 1938 could be produced and sold. The 200 trucks and 2,600 wagons for the transport of beer and barley were mostly confiscated, but without ever being used in the war. A total delivery stop could only be prevented with great effort. It is thanks to the great business management skills of Manfred I that a 7 to 8 % dividend could be paid out by the end of the war. He also made sure not to let the brewery’s surpluses flow into the financing of the war, but invested them in a collection of paintings which was secured against monetary devaluation. In doing so, he was careful not to acquire any Aryanized pictures, which proved very useful after 1945. It turned out that the paintings were supposed to provide valuable services, but would later also ensure that the representation rooms were appropriately furnished. In May, 1950, he was proud to announce that the value of those artworks was 4.7 million schillings (almost 4 million euros) and had achieved three times the value of other investments.

After Manfred I had succeeded in relocating his wife and daughters to St. Martin near Grimming in Styria at the beginning of 1945, on his way back he got caught up in the final fighting between the German and Russian armies in the west of Vienna and only reached the city by long detours and good luck. He spent the end of the war in his house in Simmering (which was then burned down during the fighting), but then immediately drove to Schwechat, where the “Wehrmacht” and the Russian army had fought a grenade launcher battle over the factory.

1945 – reconstruction and expansion; Manfred I had shaped the history of the “Schwechater Brewery” for three decades

George III had fled from the Russians to Brazil via Switzerland in 1945, he wanted to leave Europe because he had given up all hope of the survival of his company. When he returned to Vienna for the first time in 1949, he became chairman of the supervisory board and, from 1968 until his death in 1982, honorary chairman of the brewery.

From the very beginning, Manfred I was an outstanding businessman and leader. After the end of the war he was not afraid of the Russian occupiers and on May 24, 1945, a few weeks after the end of the clashes, he took over the management of the company again “de jure”, as he had been appointed by the Austrian State Office for Industry, Commerce, Trade and Transport as the public administrator of his own company. The most pressing issue was that the Soviet occupying power could not exert any influence on the brewery. Since 92 % of the shares were in Austrian hands, it could easily be proven that the brewery was not part of “German proprietorship”. Some of the executives, including the chairman of the supervisory board, Karl Dittl-Wehrberg, had fled to western Austria when the Soviet army marched in. So Manfred took over and fulfilled for almost five months all the tasks of the supervisory board, the board of directors and the general meeting. It was only when conditions were halfway normal again that he called an extraordinary general meeting on October 9, 1945, at which his father Theodor I was elected chairman of the supervisory board and his brother Gerhard as deputy. As a result, the appointments for the chairman of the supervisory board, the chairman of the board of directors and their deputies were at least unique in Austrian economic history. Until 1978, for 33 years, there were only members of the family in those positions.

Immediately after the end of the war, the reconstruction of the brewery began; one fifth of the buildings had been destroyed. Although there was still some beer remaining, almost everything had to be delivered to the occupying powers, which is why even the Russians were very interested in the smooth operation. Of the 1.5 million barrels from the pre-war period, just 400,000 and of the three million bottles only 250,000 could be saved. Instead of 280 trucks, only 29 were ready for use, but for a long time there was neither fuel nor tires for them. So Manfred had to use unorthodox methods and sold a painting by van Dyck to a Swiss entrepreneur for 96 truck tires in order to be able to get the vehicle fleet back on the road. There was enough hops available, but the shortage of malt, sugar and coal only allowed for a small amount of production (on June 28, 1945, for the first time, it was possible to brew again small quantities). The struggle for available raw materials was immense and everything depended on the negotiating skills of Manfred and his general manager Otto Wanke. At first, they were procured from the Simmering company (“Vereinigte Hefefabriken Mautner Markhof & Wolfrum AG”), where larger remaining stocks from wartime were stored. Since no one suspected that a malt house was working in the yeast factory, they could still be processed unnoticed by the Allied military authorities.

As early as on August 8, 1945 Manfred chaired the first meeting of the newly constituted Association of Austrian Breweries and was its chairman until 1965, making him the most powerful man in the Austrian brewery industry. It is also thanks to him that the brewing conditions were restored to order relatively quickly in the post-war years. In that association, which also represented the breweries as a professional association in the Chamber of Commerce, Schwechat, Göss, Reinighaus, Stiegl, Ottakring and the “Brau AG” jointly regulated all problems in the context of the beer cartel since 1948 and thus formed an oligopoly that dominated the entire market. However, since the government largely prevented the barley from being used for brewing operations, he was still hardly able to get a grip on the enormous problems of using raw materials. Barley had been declared a bread grain by the Allies and there was a prohibition on malting, which was linked to a ban on the allocation of coal.

In the winter of 1947, production and sales of beer had to be suspended for three months, mainly because of the power failure. From the minutes of the working committee, “The grotesque thing about our current situation is the fact that despite the great demand one has to speak of a success of the sales department if it manages to keep sales below 35,000 hectolitres per month.” If beer were delivered, then it would be delivered only to important organizations, to certain factory kitchens and to heat-endangered companies, but hardly to inns. The “Volksstimme” reported that on warm days, long queues wait in front of the inns for beer to be served. It usually doesn’t take long and a board appears on the bar and on the front door: “No beer”.

Although the shortage of raw materials was still clearly noticeable, conditions improved in 1948, which is why Manfred decided to resume bottled beer sales in order to bring 7.5-grade beer onto the market for the first time. It is thanks to Gustav I’s exemplary sales organization that the delivery and collecting of kegs away from the brewery and back was limited to just four days (which no other large brewery could manage).

Thus the dying of breweries in Vienna was advancing. The final phase started in 1950, when the “Nussdorfer Brewery” was acquired from Wolfgang Bachofen Echt for around 10 million schillings, partly in cash and partly in “Schwechater” shares. For that, the share capital of the “Schwechater Brewery” had to be increased to 21 million schillings and a representative of the Bachofen Echt family moved into the supervisory board. Finally, in 1959, after the “Rannersdorf Brewery” was sold to a brewery consortium, only Schwechat and Ottakring remained as independent breweries in the Vienna area. Overall, it is said, the Schwechat Brewery was at least partly responsible for the closure of 15 breweries in Vienna and the surrounding area. It should be mentioned briefly that in 1949 the Soviets opened only for their USIA (administration of Soviet assets in Austria) stores their own brewery in a Schwechat malt factory. However, that Russian beer was extremely bad and so Manfred was able to persuade the USIA to sell the “Schwechater” beer at a cheaper price than the rest of the retail trade. In doing so, he eliminated that competitor before the Austrian State Treaty was signed.

In order to have enough cash available, many properties were liquidated in the post-war years: the grounds of the former St. Marx Brewery, which was destroyed by bombs, the properties of the merged Nussdorf Brewery, the Dreher Park in Meidling and the war-damaged house of the brewers’ association in Kärntnerstraße 23, which the family had acquired after self-winding up of the association in 1938. The properties of the St. Georg`s brewery’s was not sold to the municipality of Vienna until 1970. The company headquarters remained in Simmering for the time being, because if the headquarters had been relocated to Schwechat, they would have changed to the Russian occupation zone. In the first two post-war years alone, 17 million schillings were used for the reconstruction, which was not finally completed until 1957, the year the brewery’s 325th anniversary was celebrated.

From the commemorative publication, “On the occasion of the anniversary […] on May 19, 1957, a beautiful celebration united the management and all employees and workers of the company. Chancellor Ing. Raab appeared in person and in his speech expressed his joy at being able to congratulate such a flourishing Austrian company on its 325th birthday.” Many decorations for services to the Republic of Austria were awarded and “with those awards they did not only honour those to whom they were presented, but all those who did their best to rebuild the brewery and thus to the Austrian economy in the difficult years after the war.” […] “The huge silo, which was built between 1939 and 1941 contains a storage space for 1200 wagons of grain or malt, and rises high above all other buildings. 40 silo cells with a capacity of 280 to 300 t each, equipped with the most modern ventilation devices, air conditioning and drying systems, and a grain conveyor with a large capacity are of decisive importance for the storage of the important raw material barley. A light control room ensures a clear control and the monitoring of the entire system through automatic display of the machines in progress and activated transport routes. The central switch-on and switch-off option for entire processes and the automatic switch-off of individual machines in case of malfunctions ensure smooth handling of all work processes and come very close to automation procession. Electric remote thermometers enable temperature control in the individual silo cells and measurement of the outside air, which is also checked for moisture content by electric hygrometers.” The new brewhouse was also completed shortly beforehand, “Its elegant architectural design demonstrates, that it is possible to carry out aesthetically flawless industrial buildings that have to fulfil purely technical tasks. The brewhouse is the heart of every brewery. The play of colours of the huge copper mash pans and the wort pans elicits astonished admiration from the layman and fills the heart of the expert with joy.”

The brewery had expanded in a northerly direction and was given the address Mautner-Markhof-Straße 11.

1957 – the heyday of the 2nd republic begins

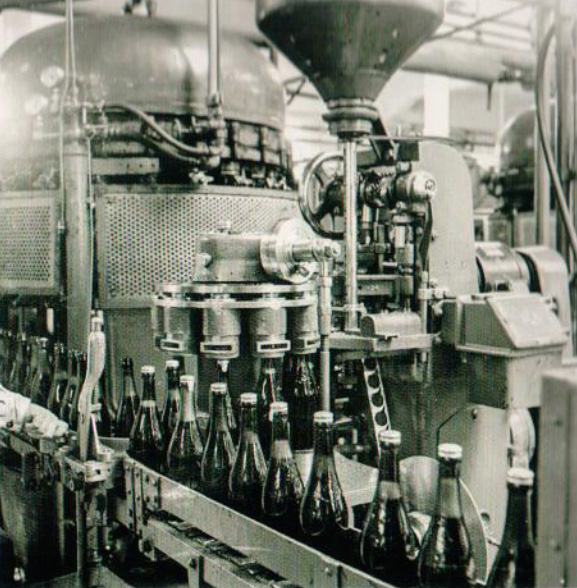

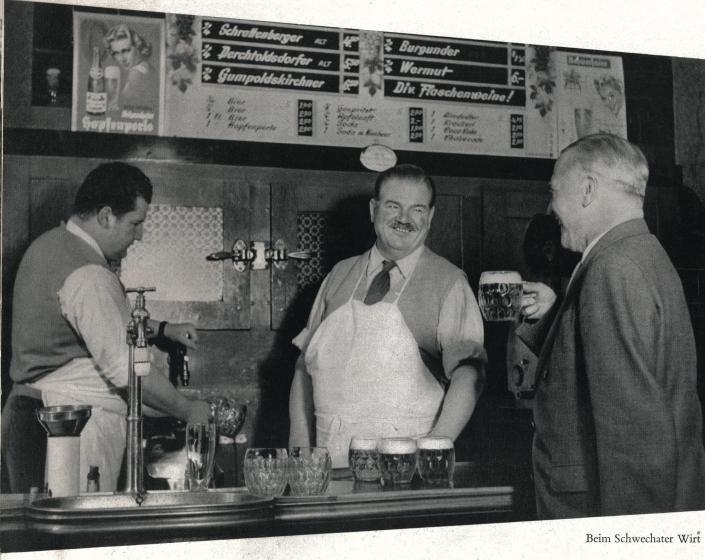

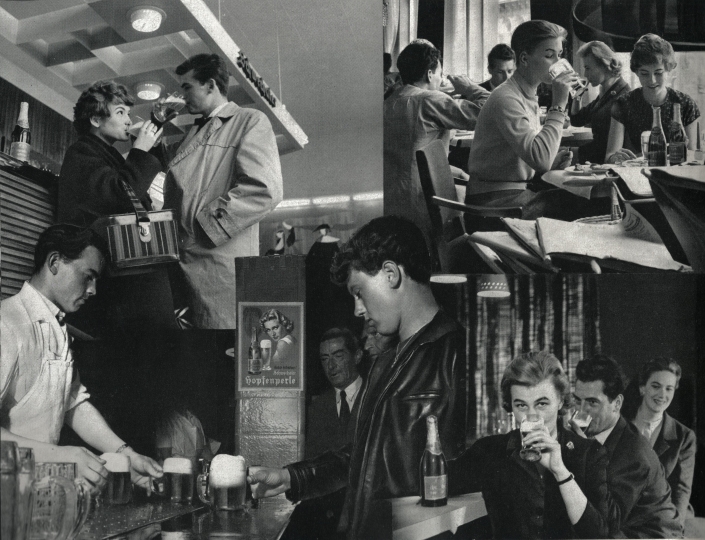

The construction of the new brewhouse made it possible to double the capacity, the bottling plant had already reached an output of more than 100 million bottles in 1958 and the construction of the new malting plant began. At that time, the brewery had around 50 beer depots in Austria. The “Hopfenperle” brand had been reactivated as a special beer as early as in 1955, especially in the 1/3 l bottle, and in the early 1960s the 1 million hectolitre limit was exceeded again for the first time (that output could be continuously kept without exception until 1978). When the Danube Tower was built in 1964, the brewery took a 25 % stake, which means that the stylized Schwechat beer glass was at the top for many decades.

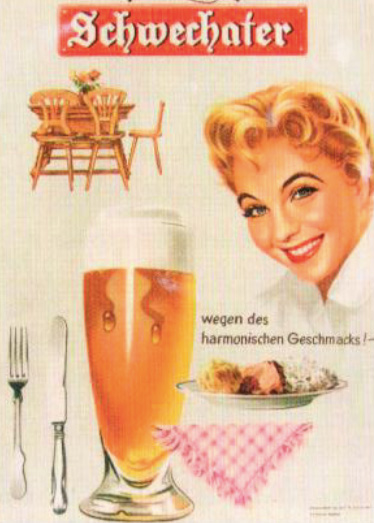

At the same time, however, there were also major changes in the market. In Vienna and Lower Austria, beer sales declined due to the dying out of inns, the long holiday closures in summer, the changed leisure habits of townspeople, television as a new evening activity and increasing competition from the Styrian breweries. The western Austrian breweries with “Brau AG” at the top benefited from the increasing tourism, so that the market shares shifted more and more from the east of Austria to the west.

In 1967, in his last year as chairman of the board, Manfred I achieved a so-called “all time high” with a record output of 1.3 million hectolitres. One invested in “SKOL International Ltd.”, under whose form Manfred II produced the new world-wide sold beer of the same name (when English brewing bosses took over command of that enterprise, the family sold the stake at a profit and, as a founding member, had benefited from never having to pay license fees). In 1968 Manfred I handed over the chairmanship of the board to his long-time colleague Gustav I, who died two years later, so that Manfred II took over at the top of the enterprise in 1970.

In the non-alcoholic sector, the enterprise had a successful share in the mineral water producer “Güssinger”, it produced well-known lemonades such as Soma and was one of the first breweries to bring out an alcohol-free beer (the production of which was discontinued after the merger to form the Brau Union). Manfred II and his technicians had developed a process with which beer could be produced as a concentrate. From the memoirs of Manfred II, “It was quite far developed, you could have added flavourings, but basically the product was finished and no difference to conventional beer was noticeable. Our “test market” would have been the Soviet Union, and so we had to explore that market.” The Russians lost interest in being “guinea pigs” so there was no further activity in that area. The “Schwechater Brewery” was also often one step ahead of the competition when it came to launching new trading units. They were one of the first to introduce the Euro bottle and the first to replace the wooden boxes and barrels with the much easier-to-care-for ones made of plastic or stainless steel. At that time there were 13 million euro bottles and 800,000 plastic crates in Schwechat – in 1913 Anton Dreher had still worked with only 5 million bottles. The “Steffl Braugaststätten GmbH”, founded in 1973 and later renamed “Lembacher-Restaurationsbetrieb GmbH”, was intended by Manfred II as a rescue company for financially suffering catering outlets. The renowned Coq d’Or was acquired as the first restaurant. However, a pure rescue company subsequently turned out to be unnecessary, as the majority of the other companies, after painful initial losses in the early years, could, in the course of time, be converted into properly profitable businesses. However, one continued to be active in the gastronomy: the long-standing restaurants in the “Schwechater Hof” (formerly Dreher’s Etablissement), the “Goldene Kanone” in Linz (which had the highest beer sales of all restaurants in the 1970s) and later also some bars in the “Shopping City Süd” were run. Finally, the brewery was also able to build new hotels such as the Holiday Inn in Innsbruck through cross-shareholding.

1978 – The “Brau AG” becomes majority owner of the “Schwechat – Brewery AG”

Since Gerhard and Gustav I died within just six months, the Mautner Markhof family’s long-proven management style, the “Viererzug” (four heads of families jointly manage the business of all family businesses), had to be formally dissolved at their 352nd meeting in February 1973. For the first time, all family members who owned blocks of shares in the Schwechat Brewery AG were able to vote in person according to their voting rights.

Since the family no longer owned the majority in the Schwechat Brewery at that time, the “St. Georg Verwaltungs- und Beteiligungs AG” was founded in order to be able to form a united block of shareholders. The families who had been friends for a long time Meichl, Bachofen Echt and others joined that investment company. St. Georg bought shares (including those of the “Girozentrale”) until it owned 51 % of the Schwechat Brewery. In the 1970s, four large brewery stock corporations competed for the Austrian market and ran various cooperation scenarios: the Schwechat Brewery AG (represented by St. Georg AG), the “Österreichische Brau AG” (under the management of the Beuerle family), the “Brothers Reininghaus Brauerei AG” and the “Gösser Brauerei AG” (Heinrich Treichl represented “Reininghaus-Gösser” and the “Creditanstalt”). At that point everyone was already aware that there could be no further growth, but that profits could only be generated through rationalization.

The following years brought a huge upheaval in beer culture in Vienna and Lower Austria, which had a negative effect on the “dominant male” “Schwechater”. The “Zwettler” and “Ottakringer” breweries smashed the beer cartel in 1977, which enabled the inns to offer other draft beers as well. Small breweries like “Hirt” crowded into the federal capital Vienna and also beers from in-house breweries were enthusiastically accepted. The supermarkets had never adhered to cartel borders and had always sold different bottled beers, so the Viennese more and more often did not order a beer, but decided (long before “Craft Beer” became fashionable) which one they wanted to drink. Moreover, some decisions, especially in marketing and the use of financial resources, had a negative effect without countermeasures being initiated in good time (the cheaper positioning of the main “Schwechater” brand compared to the competition had generated far too few additional sales volume than expected; the resulting lack of profit could not be balanced). In 1977 the “Schwechat Brewery AG” had to face a loss balance for the first time, and it was realized that maintaining substance and income was more reasonable than a meaningless competition. Furthermore, tough rationalization measures such as dismissing hundreds of employees would not have been possible at that point in time, as the then mayor of Schwechat, Rudolf Tonn, opposed that as the brewery’s former factory committee member representative. Therefore, in 1978 the Mautner Markhof family merged the holding company of “St. Georgs Verwaltungs- und Beteiligungs AG” with the holding company of “Brau AG”, which in turn became the majority owner of the “Schwechat Brewery AG”. At that time – measured in terms of sales – No. 30 (“Brau AG”) merged with No. 57 (“Schwechat AG”) to form the 15th largest company in Austria and St. Georg became the largest single shareholder of that “Brau Union” with a 26 % share.

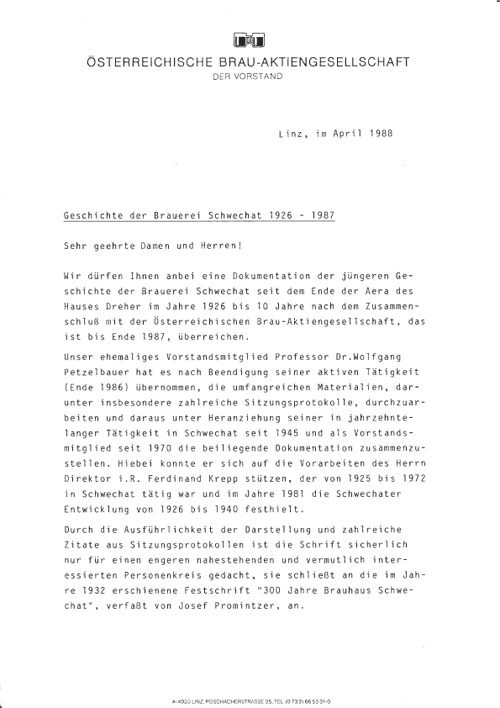

Thanks to the 25 % share of the “Creditanstalt”, which had replaced the Schoeller family as the second largest shareholder in 1970, the Schwechat brand name also remained, as did the legal form of a stock corporation, as the Creditanstalt wanted to take advantage of the tax-friendly model of a participation in an affiliated company. The general directors who initially acted together were Dr. Christian Beurle in Linz and Manfred II Mautner Markhof in Vienna. After the merger, Manfred II resigned as general director and left his position on the board of directors to his cousin Gustav. Manfred I. remained chairman of the supervisory board until his death in 1981, followed by Marius Mautner Markhof, a son of Gerhard. The merger of the two large breweries made restructuring necessary to a large extent, many beer brands and their different sales areas had to be reconciled as efficiently as possible. An attempt was made to organize “Brau AG” and the “Schwechat Brewery AG” in the same way with a uniform IT accounting system and to adapt the different corporate cultures.

In 1982, the 350th anniversary of the “Schwechat Brewery AG” was celebrated, and in the same year the bottling of mineral water and the production of Soma and soda water were stopped. In addition, new installations offered completely new packaging and design options. When “Brau AG” increased its share capital by “ATS” 28 million in 1986, the “Schwechat Brewery AG” acquired shares to the value of “ATS” 7 million while at the same time issuing own shares to the value of “ATS” 10 million in order to be able to maintain the 25 % interest. That increased the share capital to “ATS” 160 million. Finally, in 1987/88, the fermentation and storage cellar system made of stainless steel, which replaced the old tank systems from the time of Konrad Schneeberger, was constructed at a new location.

In 1998, the “Brau Union Österreich AG” was founded from the merger between the “Österreichische Brau AG” and “Steirerbrau AG”. There, the Mautner Markhof family was still the largest single shareholder with 26 %.

2003 – Brau Union Österreich goes Heineken

This was followed in 2003 by the acquisition of 33 % of the shares in the Schladming Brewery, which was increased to 90 % in 2005. When the new company became the property of the Heineken Group in 2003, General Director Karl Büche was able to ensure that the location of the brewing plant as well as the brand name Schwechat were preserved. The new owner, Freddy Heineken, had thanks to the rationalization measures that had already been taken, such a decisive lead that he was able to produce at half the price. Schwechater now is a prime example of how strongly traditional Austrian companies can be positioned in international corporations.

This and that about the Schwechat Brewery

Manfred I, following the family tradition, improved the quality of life in Schwechat with many campaigns, especially the housing shortage after the war, by building new accommodations for the employees. He financed the construction of the first children’s outdoor pool and furthermore looked after needy children in the city. He would have liked to build a hospital, but the mayor had gratefully declined in view of the large follow-up costs. Almost every family in Schwechat had at least one member employed at the brewery, so that the working environment was very familial. Around 80 people lived on the brewery site itself, and some family members grew up there, next door to the children of the cellar master, the master brewer, the electrical and mechanical engineers. Two to three cows provided fresh milk, chickens provided fresh eggs and in the brewery’s own deer enclosure you could admire a venerable stag.

***

The long-lasting image of a beer for “simple workmen” stuck to the Schwechater mainly because of the popular series “A real Viennese never gives up”. In almost every episode, the actor Karl Merkatz as the character “Mundl Sackbauer” opened his beer bottle by loudly tearing the typical Alka cap, which was only replaced by the brewery in 1979. Schwechater was one of the last to replace this classic closure made of aluminum, which, because it was often not airtight, sometimes caused problems with hygiene.

***

Under the management of Manfred II Mautner Markhof, the company became the first shirt sponsor of FK Austria Wien in 1967 and thus the first shirt sponsor in the Austrian soccer league; As Austria President until 1971, he also represented the corresponding link between the club and the company.

***