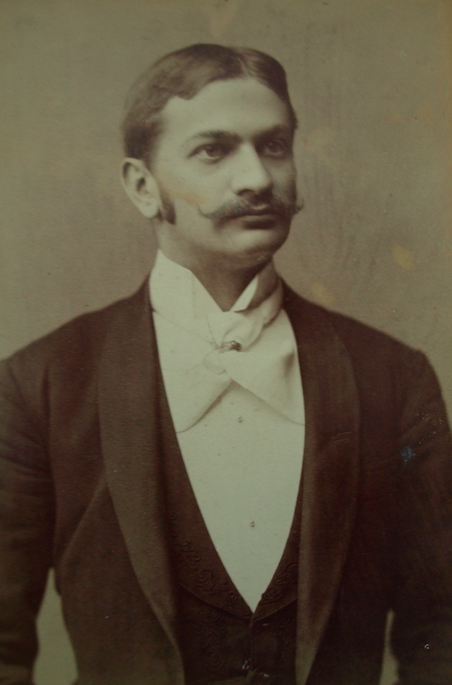

Victor Gottlieb Johann Ritter Mautner von Markhof / 5.7.1865 – 10.5.1919

Victor was born in Vienna as the second child of Carl Ferdinand and his first wife Johanna Leopoldine Kleinoschegg. He had six full sisters and, as a result of his father’s second marriage, three half-sisters. His training was conventional, he studied at the Technical University in Vienna and graduated from the brewery and agricultural college in Weihenstephan in Bavaria. When he was seven years old, Adolf Ignaz was ennobled, and so he got to know the life of the privileged in early years.

In contrast to his grandfather and father, he already grew up in prosperity and found his perspective life less in work and development than in enjoyment and consumption. This may also have been one of the reasons why Carl Ferdinand extended the continuation of paternal violence by the nursing authority indefinitely in 1889, although Victor was already 26 years old at that time. (Amtsblatt zur Wiener Zeitung, May 14, 1889, 696)

It is undisputed that Carl Ferdinand also sensed his son’s lack of interest in the company management, because he tried to get his son-in-law Ludwig Schürer von Waldheim, the husband of his daughter Cornelia, enthusiastic about the brewing trade and the cooperation. However, the latter could not make up his mind at first and then died much too early in 1894. Carl Ferdinand then even planned to bring the brewery into a public limited company, but death preceded the implementation. (Neue Freie Presse, December 13, 1896, 10)

Victor, at the age of 41, was the only son to inherit the St. Marx and Simmering businesses where he had worked for about 20 years. From 1906 to 1909 he was president of the brewery association like his father and on no account, you can say that he did not know anything about the brewing business. After Carl Ferdinand’s death, however, he had to pay off his nine sisters, which, of course, encountered considerable difficulties and put a heavy strain on the company’s budget. The family also expected excellent performance from him, since the production figures of Anton Dreher jun., who managed the Klein Schwechat brewery just a few kilometers away, had to be exceeded. In 1910, he almost hit the target with 560,000 hectoliters (just 2 percent behind Dreher). But the technical equipment became more and more obsolete and the adapted monastery buildings became increasingly dilapidated, so that St. Marx had to be closed during the First World War, 1916. Perhaps it would have gone better if he had had a top manager like Alfons Erhard working for him, who had come to Vienna as a 24-year-old and started with Victor’s father in the St. Marx administration. A year later, however, he was headhunted by Anton Dreher, managed first his and subsequently the United Brewery for many years with great success. From 1908, he became the first non-member of a brewing family to become president of the brewing association and thus a very influential man in the Viennese brewing industry. (Paleczny, Die Wiener Brauherren (Anm. 1), 75). Looking for another partner, Victor tried to build up his cousin Kuno (Georg Heinrich’s youngest son) as a future successor from 1900 onwards. But even the then 21-year-old preferred to focus more on going clubbing life than the management of the company. Only later did he develop into a recognized brewing scientist and held the office of president in both the Austrian Experimental Station for Fermentation and the Austrian Brewers’ Association. After Victor’s death, he was his successor in the United Brewery until the family had to give up their influence on the board of directors.

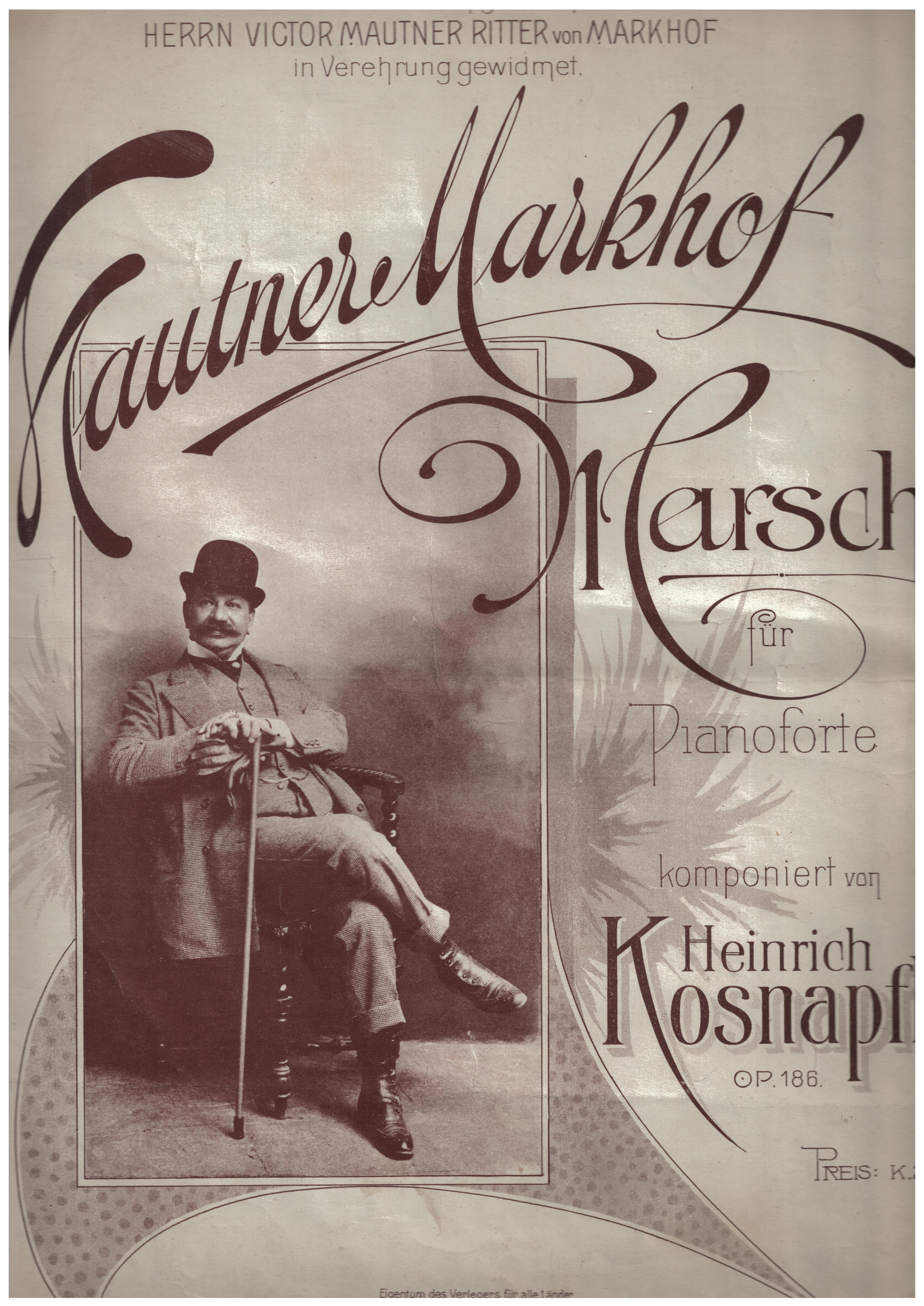

He was constantly exposed to a comparison with Anton Dreher. This produced the highly acclaimed lager, Victor produced the draft beer known as the low-alcohol “folk´s beer”. Dreher was President of the United Brewery, Victor was only Vice President. Dreher had three sons, Victor remained childless. When he heard that his competitor had ordered a “Dreher March”, he ordered a “Mautner Markhof March” from a relative of his wife. Even with his greatest passion, horse racing, Dreher was always a step ahead for years. When he won the Vienna derby with his wonder horse San Gennaro in 1917, he had only achieved what Anton Dreher had already done twice before. Dreher was a member of the board of directors in the feudal jockey club, Victor was only accepted into their racing committee shortly before his death.

It is undisputed that he felt more comfortable in equestrian sport than in the brewery, which is documented by countless newspaper reports. He initially devoted himself to sporty racing with carriages, which was very popular in Vienna until the 1890s. Besides Prince Esterhazy, he was the only one who only put white horses in front of his carts. Later he set up a thoroughbred stud at Marchegg, whose horses in Freudenau very often appeared as winners of various races, especially in the war years. His jockeys were dressed in white with a red sash and sleeves and a blue cap. During that time, he was the most successful racing stable owner and was able to achieve the highest profit amounts each year between 1912 and 1918. In 1917, he won almost a million crowns and in the last year of the war in 1918 with 788,000 crowns, twice that of the Rothschild family’s second-placed racing team. (Fremdenblatt, February 16, 1919, 19) Unfortunately, he died only a little later, and the value of the money was almost completely destroyed by inflation.

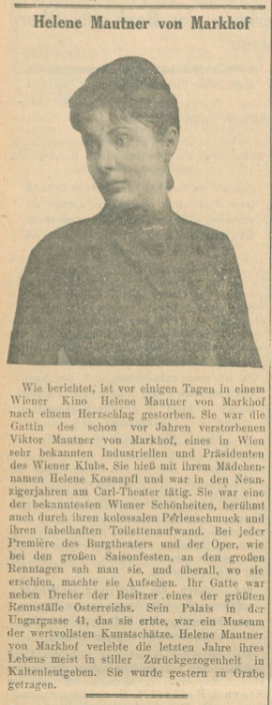

Since, of course, Carl Ferdinand wanted his only son to marry into money because of the spirit of the times and the newly gained social status, Victor had to wait until after the death of his father to marry his great love, the soubrette Helene Kosnapfl. Although Helene had smaller engagements in various Viennese theatres, she was more of a lady of the life than an artist. When Victor was sent on a trip to America by his father, he had her succeeded so as not to be separated from her. After the marriage, he moved with Helene on November 24, 1901 to the Sternberg Palace in Ungargasse 41 – 43. Helene was one of the best-known apparitions on the racetrack, her wardrobe was always closely observed by the press and commented on in almost every issue of the “Salonblatt”.

Not only was money invested in equestrian sports and social life, Victor was also very keen on continuing the nonprofit legacy of his grandfather and father. With the Mautner Markhof Foundation, he continued to look after the promotion of the health system, for example, by buying the first X-ray apparatus for his children’s hospital in Vienna. He paid his employees a double monthly wage for the Emperor’s anniversary in 1898 and spent 50,000 guilders that year on social benefits. Even though he was no longer able to match the donated volumes of his ancestors, he financed a war hospital for 100 wounded people at his own expense (at a time when he was said to be ready for bankruptcy) in his stud farm on the Markhof near Marchegg.

Because of his nobility, friendliness and generosity, Victor was also highly valued in Viennese society. He was a popular figure and an elegant playboy. If you read the newspaper reports about him, you have to conclude that he was not only one of the best known, but also one of the most successful citizens in the last years of the monarchy. In 1910 his annual income was more than 1.5 million crowns, while the cousins Georg II Anton and Theodor I took the ranks 216 and 267 of the richest Viennese with 200,000 and 300,000 crowns. But unbeaten here, too, Anton Dreher with 2.6 million crowns, the seventh highest annual income at that time. His high profits from horse racing hardly played a role, because these were only achieved after 1912. (essay Roman Sandgruber)

Family members commented on his passion for gaming as follows, “One should not always criticize Victor’s passion for gaming. His, sometimes immense losses have given the family a reputation for being rich. In a sense, it was he who really made the family popular.” (Manfred I Mautner Markhof, Haltestellen und Stationen in meinem Leben) “Victor is a gentleman. On some even-ning he gambles away huge sums of money without batting an eyelid. Because of his father’s inheritance, he can easily cope with such losses.” (Georg J. E., Von Irgendwo in alle Welt) “If he had really gambled away his fortune, he would not have been able to pay off his nine sisters or leave them so much behind. As already mentioned, my uncle had a well-known racing team and horse breeding. Like most wealthy gentlemen of his time, he was a member of a club where you could safely play for large sums – which he could afford and therefore did not lose his fortune. I feel I must clarify this matter, as I am probably the last family member to have experienced this time as an adult.” (Victor´s niece Maria Blühdorn née Schenk zu Castel, Familienchronik Carl Ferdinand)

There was a family conflict with his cousins (Theodor I and Georg II) when Victor merged with Dreher and Meichl on June 23, 1913 against their will. Victor saw no future for St. Marx because of a tax arrears of 1.5 million crowns, lack of an heir and due to his serious illness. He sold the “Floridsdorfer”, the Simmering press yeast factory, which his grandfather was so proud of, but not the brewery, which they would have liked to continue to run independently or to merge with St. Georg. Anton Dreher became President of the Board of Directors of the United Breweries, the Mautner Markhof family, until 1926, appointed with Victor and after his death with Kuno one of the Vice-Presidents. From today’s perspective, this decision saved Adolf Ignaz’s legacy because St. Marx would not have survived World War I without a merger, and as a result, there would have been no opportunity to buy back the United Breweries in 1936. In 1916 Victor had to watch the last beer barrel being filled with thin beer due to the war. Then the production was closed for all time.

Victor certainly was the most unfortunate figure in Vienna’s brewery history. He failed due to the expectations that he hardly could cope with, but was born into. (Paleczny, Die Wiener Brauherren) He was seriously ill in the last years of his life and had to undergo some operations, so that his death was seen as a salvation from the severe suffering.

Much of his fortune was, of course, brewery stocks (the rest of the stocks were mostly valueless war bonds). In addition, he had valuables worth half a million crowns (pictures, antiques), the house in Ungargasse and the Markhof stud near Marchegg with about 60 horses, which after deducting liabilities still represented a value of 1.5 million crowns. Helene was unable to continue this quite lucrative stud farm and quickly sold it for five million marks to two German racing team owners. According to his will, he suggested that his wife should sell the approximately 33,000 shares (then worth approximately 11.6 million crowns) of the United Breweries to Anton Dreher in order to pay his total debt of approximately 6 million crowns from the proceeds of this transaction. The leftover 4.5 million should remain his wife’s unrestricted property, but with the addition that after her death the inherited (but not her own current fortune) up to 1/5 of the value that she could freely dispose of in her will, should be passed on to his six full sisters or their legal successors. This left a significant portion of the shares blocked so that they could be paid directly to his full sisters after Helene’s death. In the estate essay, there are numerous submissions to the Commercial Court, especially by the elder sisters, who wanted to get those shares as quickly as possible and wanted to sell them. Almost all of the sisters had been widowed in the meantime, so the conclusion suggests that on the one hand they wanted to sell out of financial hardship and on the other hand out of lack of interest in the company and wanted to continue funding the high standard of living they were used to before the First World War.

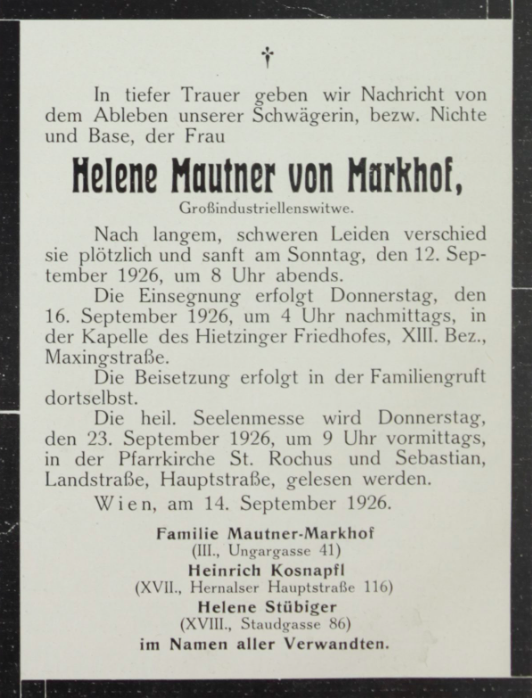

The estate of his widow Helene, who died in 1926 during a film show, was auctioned a year later at the auction house for antiquities Glückselig GmbH. A Spanish ivory Madonna (being the most expensive item), 92 paintings by old masters (including pictures by Van Dyck and Jan Brueghel), 154 paintings by new masters (including pictures by Gauermann, Jacob Alt, Makart and Pettenkofen), 130 decorative objects and furniture as well as sculptures came under the hammer. As Helene herself had no heirs, Victor’s sisters also benefited from these assets. In the 1930s, they sold the brewery shares at a ridiculously low price, so the family almost completely lost their influence in the brewery for many years. They received only 24 percent nominal value for their shares, although 70 percent would have been appropriate at that time. Indeed, stocks suffered heavy price drops in the early 1930s.

Carl Ferdinand, his two wives, Victor and Helene are buried in the family crypt at the Hietzing Cemetery.