A Tankard full of Memories – Two centuries of Vienna Lager

Words Bruce McMichael

Noisy, smokey and stinking of the streets, the tavern shakes as greetings echo around battle-weary soldiers, prostitutes and drunks, all demanding more … more music, more food, more beer. They were drinking dunkels, dark German-style lagers made through top-fermentation techniques with similar taste profiles to Belgian Dubbels and English Porter.

We’re in late 1830s Vienna, the soon-to-be capital of the sprawling Austro-Hungarian Empire. It’s a city of intrigue, betrayal and dingy coffee houses with a reputation for serving the worst beer in Europe. Production is fractured, brewers disinterested, ingredients low quality. Disguised with herbs and spices ranging through ginger, laurel, and rosemary, contemporary sources report tankards of foul smelling beer, and lots of flatulence.

Into this bleak social landscape came Anton Dreher Snr, scion of a local brewing family whose beer production and finances were both struggling, along with my ancestor, Adolph Ignaz Mautner Markhof a mutton chopped brewer and Dreher Snr’s main competitor as soon-to-be Beer Barons.

Brewers such as Dreher Snr and Mautner Markhof were 19th century beer-nerds, curious about the science of brewing and happy to get stuck into the rough and tumble of commerce. For decades, these two sparred for technological and commercial advantage, until the Dreher family lost interest and Mautner Markhof’s descendents absorbed Dreher’s prime Schwechat brewery into their own operations.

Fast-forward to the 1970s and it is endless supplies of cola and fizzy orange that shape my earliest memories of childhood holidays with my maternal grandparents in Vienna, and visits to extended family living in the Schwechat brewery. But as I grew into my teens, the beer made its appearance: my brothers and I secretly flipped open bottles we found in cellars and store rooms pursing our lips as we sipped the bitter Vienna Lager.

It was common for young brewers in the early 1800s to travel and work across Germany, Belgium and Britain. In search of knowledge, Dreher Snr and his friend and business partner Gabriel Sedlmayr from Munich’s famous Spaten brewery, took to the road – and they didn’t care how they got their information.

British industrialists were notoriously secretive, but nonetheless – perhaps naively – welcomed the pair into their breweries, where the ambitious friends embarked on what can only be described as industrial espionage, including using an adapted walking cane to steal away liquid samples.

At the start of the nineteenth century, British breweries had began using heated air to dry the malt, achieving an evenly roasted product with little scorching. Returning to Vienna, Dreher Snr experimented with British kilning methods, creating a lightly caramelised amber malt. He called it Vienna Malt, mixed it with lager yeast and brewed a reddish-copper lager with a delicate, slightly bready profile reminiscent of British pale ale. The beer was released in 1841 as ‘Lager Vienna Type’ or Vienna-style lager, and so started Vienna’s Golden Beer Century.

The Lager’s superior structure and flavour immediately appealed to the jaded and abused palettes of the Viennese, offering a cleaner, fresher taste. The resulting morning sore heads were soothed with reviving breads such as the Kaiser-Semmel, a hugely popular sweet, white, segmented roll. Viennese bakeries had long done good business, using copious amounts of fresh yeast, easily available from top-fermented ale production popular in pre 1840-Vienna.

Production of Vienna Lager, however, posed a problem. Bottom-fermented lagers like Dreher’s did not produce fresh yeast, Viennese bakers were soon short of supplies.

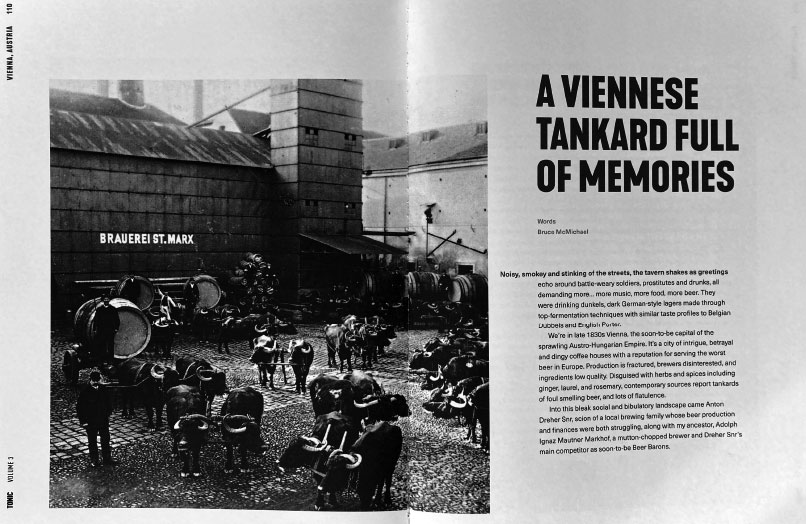

Into this culinary emergency stepped Adolph Ignaz Mautner Markhof supported by his sons (he had ten children and 72 grandchildren). Renting breweries in the districts of St. Marx and Floridsdorf in 1848 Adolph Ignaz partnered with his sons-in-law Julius and Peter Reininghaus in the southern Austrian town of Graz. Together they developed a brand new process to produce yeast strains from bottom-fermented tanks (pressed yeast) – a system that became informally known as the ‘Mautner Markhof filter yeast process’.

The bakers were not slow to show their gratitude. This pressed yeast won a huge cash prize from the powerful Viennese Bakers Guild. A fortune quickly followed which – riches that made possible the purchase by the Mautner Markhof family of Dreher’s original Schwechat brewery in the late 1920s during the global financial crash.

After the economic devastation of World War 1 Vienna Lager never regained its status in its home market, with the Viennese turning to wine and other brews.

However, in the early 2000s, North American craft beer revivalists began dusting off recipes for this forgotten lager, inspiring a handful of breweries in Austria and the UK to follow. They have produced a choice of palatable drinks with robust malt, clean yeast characters, and a light amber colour shot through with the red of the original Vienna Lagers.

It’s a welcome revival of this very particular beer – along with a crate full of memories from my family history.