For Marceline Bertele von Grenadenberg – a monument to the best of mothers

I think I can say on behalf of all six of my siblings – living or deceased – that we had the best and dearest of mothers. My gift to her, for Mother’s Day 2023, is that I am trying to memorialize her with my words. My mother Marceline, who simply meant everything to her husband and children. She was also always devoted to her many relatives with love and generosity. I can express no more beautiful wish than that I wish every husband and every child a wife and mother like Marceline.

![]()

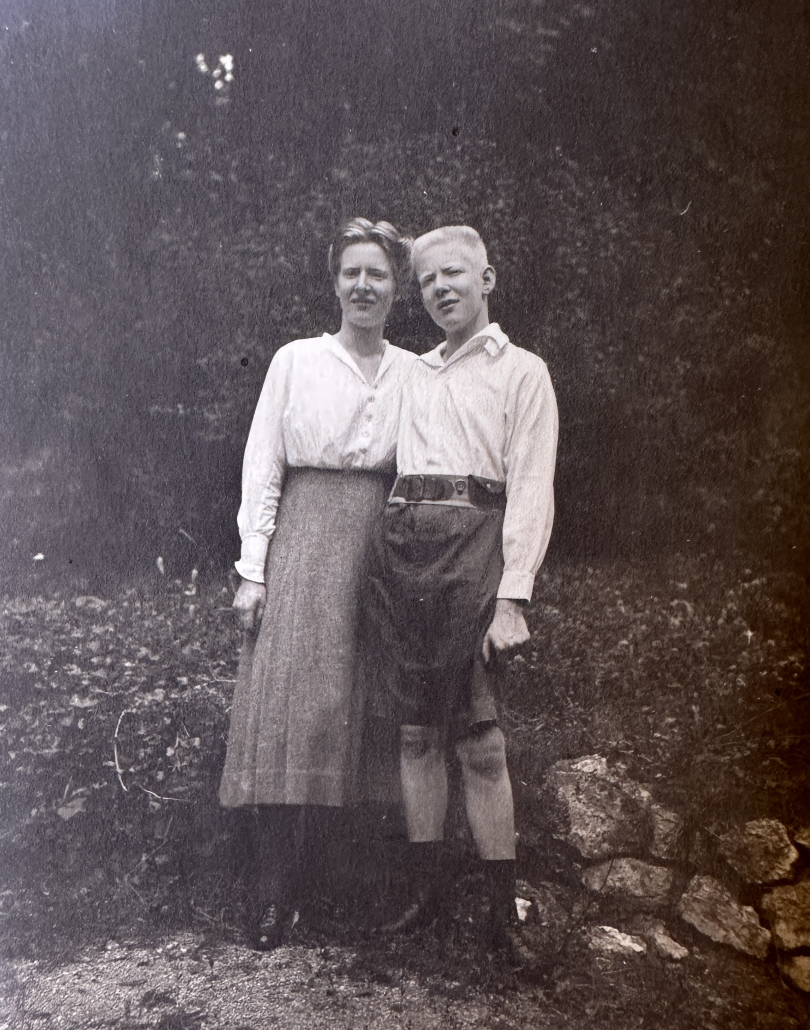

Marceline, eldest daughter of Georg II Anton Mautner Markhof and Emy Reininghaus, was born on May 3, 1901. She grew up in Vienna/Floridsdorf, in the beautiful Mautner villa with its large garden. She was given a French governess and educator – called Maury – quite early on. As a result, Marceline soon spoke perfect French. As far as we know, she never attended a public school.

When Marceline was still very young, there had once been concern that her lungs might be damaged and that she might suffer from tuberculosis, as was often the case in those days. Her father himself had taken her to a health resort, I think in Semmering, where she recovered completely. Marceline always had the greatest admiration for her father. One of her memories of him was a trip to Venice that he had taken her on. More than the magic of the magnificent buildings and the unique location, she had depressing memories of the sad decay, decadence and stagnation of the city.

Marceline always had an extremely good and loving relationship with her six siblings. She had great respect for her brother Buwa throughout her life. Even later, when it came to sensitive issues concerning our Bertele family, she consulted him and followed his advice.

Just like her mother, who was passionate about breeding smooth-haired fox terriers and taking them to shows, Marceline had a love of dogs. Later, she also became an enthusiastic horsewoman. She owned a beautiful chestnut-colored mare that she named Goldie. She rode her all over the floodplain and up the Bisamberg.

She was in no hurry to get married.She loved the intimate family life in Floridsdorf and the summer months that the family spent in Baden, in one of the beautiful family villas in what was then Berggasse (now Marchetstrasse) I think No. 72 – and her passion at that time was also for horses. Once she had a bad fall, Goldie had gone off for some reason. She was unconscious for a worryingly long time with a concussion; when she had recovered, she rode on happily.

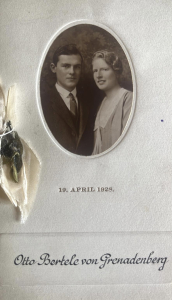

My parents’ great love affair began in February 1925 when they met at a house ball at Palais Dumba. The following fall, the two of them went on many wonderful outings together. Marceline always brought good home-made bread with ham topping, which Hans, who always had an appetite, ate with great relish. On one of these wondrous autumn days, the couple took a walk in the Spillern floodplain and from there up to the fairytale Kreuzenstein Castle near Korneuburg. There they first talked about the future, then about a good way of living together. They got engaged that afternoon. As they said goodbye, Marceline said loudly and firmly: “Good night – everything is very good, but I want lots of children.” To which Hans replied just as firmly: “Me too, good night!” Soon afterwards, Hans made the official marriage proposal in Floridsdorf. Georg Anton received him very kindly and said at the end: “Always remember, marriage is a work of art that you spend your whole life building, sometimes hard on one, sometimes hard on the other.” Words that he had already impressed upon his daughter. As Hans and Marceline were already engaged, she wanted to meet her future father-in-law as soon as possible so that she could see that he was neither bald nor wore glasses. Hans’ father may have been short in stature, but in the two respects that Marceline attached so much importance to, he fully complied with her wishes: no bald head and no glasses, although he was already seventy-one years old. The wedding took place on April 19, 1928 in Floridsdorf. Unfortunately, I can’t tell you anything about it. I’m just lucky enough to still have my grandfather’s menu card. It has a wonderful photo of the happy young couple.

Extract from Hans von Bertele’s memoirs

Our wedding was on April 19, 1928; the ceremony took place in the small parish church in Jedlersee; Marceline and I drove there and back in Mautner’s horse-drawn carriage. Then there was a festive, large wedding dinner in the beautiful house in Floridsdorf, Pragerstrasse 20; afterwards all the guests were photographed in front of the house on the stairs – nicely grouped together. The weather was not very nice, but cool and cloudy; unfortunately the beautiful magnolias behind the house in the park were not yet in bloom. Then we drove to Semmering by car, stayed there for a day or two and from there the actual honeymoon began by train. The father-in-law had prepared a beautiful sea voyage for us on the ship Ozeania (approx. 4000 tons). We took the sleeping car to Genoa; when boarding at Semmering, my small travel bag dropped on mom´s head, but that didn’t disturb the friendly atmosphere. We traveled by ship from Genoa via Corsica, via Palma de Mallorca, Málaga with a short trip to Granada, via Gibraltar, via Lisbon in Portugal, and the Isle of Wight to Hamburg; in Hamburg we stayed at the Vier-Jahreszeiten, had a good meal there at the Uhlenhorster Fährhaus, traveled to Magdeburg for a short visit to the Baensch and back to ViennaFor the next few months we lived in the Stöckl in Floridsdorf; in the meantime Marceline and her mother tried to find an apartment in Vienna, because finding an apartment in Vienna wasn’t easy back then. Marceline had the sensible view from the outset that the apartment should not be far from my workplace – the Elin company – Volksgartenstrasse 1.

Two years after the wedding, little Otto was born. Marceline was blessed with a large number of children, just as she had dreamed of. Her husband, Hans, was a keen mountaineer. However, after two of his companions had fallen or otherwise had accidents in the mountains and he had already fathered three children, he gave up this hobby. Marceline’s energetic pleading was probably the main reason for this. Nine months after his last big mountain tour, little Hansi was born. His father had high hopes that he would one day have a brilliant career.

Marceline and Hans spent the first years of their marriage in Lackierergasse in Vienna’s 9th district.

Extract from Hans von Bertele’s memoirs

With some effort, Marceline and her mother found a nice apartment on the corner of Lackierergasse and Garnisongasse; across the street was only a storey-high work building of the General Hospital. The various rooms in the apartment were therefore exposed to the sun from morning to evening, as the apartment was around the corner. The father-in-law ordered a very nice interior for this apartment from the architect Wimmer. We moved in before Christmas; it wasn’t finished for a long time, even though Marceline had said: “I won’t move in until the towel is hanging on the last hook!” But we had beds and a dining table, some equipment in the kitchen and gradually the apartment became as shown in the pictures.

In my book Das Haus am Froschplatz, eine Wiener Geschichte I describe how they then wanted to buy a villa with a beautiful large garden in the 19th district, which was to be foreclosed. Marceline was particularly fond of this idea – for the sake of the children. Her father, however, asked the young couple not to do it: Hans did have a good income with Elin, but it would apparently have involved liquidating funds or shares in the brewery. Times and the general financial situation had started to become increasingly difficult. My parents complied with Georg Anton’s request and refrained from buying.

Hans, the young engineer, had quickly made a good name for himself at Elin. And where there is success, envious people are usually just around the corner. In the great confusion following the annexation of Austria, he was quickly relegated to an inferior position that in no way corresponded to his qualifications by those who didn’t begrudge him his good reputation and success. However, Siemens in Berlin had already taken notice of him and so he was able to take up a suitable position in the huge company in September 1938.

The Bertele family, already with four children, moved to Berlin in September 1938, where Marceline, who was already pregnant, gave birth to daughter Elizabeth in March 1939. Hans had a very good position at Siemens and the first years of the war went well and victoriously for Germany. Soon after his arrival, he managed to buy a nice house with a garden in Schmargendorf, so the family had a fairly comfortable life. Marceline’s sister Charlotte, who was married to the handsome Georg Günther from East Prussia, also lived in Berlin. Little Elisabeth, called Liesl, had a nanny, Lena. When Liesl once crawled through the garden on all fours, digging in the earth and then sticking her fingers in her mouth, Lena said reassuringly: “Dirt srubs your stomach”, a saying that Marceline would later use again and again.

I, little Ursula, was born on December 7, 1941. A happy day for me and my family, but a fateful one for Germany, as the USA entered the war after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. A decisive turning point had begun, which would ultimately lead to Germany’s defeat.

Extract from Hans von Bertele’s memoirs

In the winter of 1941, the bombing in Berlin began, initially with incendiary bombs; once there was an impact in our air-raid shelter through the door of the small courtyard; Mum was surprisingly calm and immediately sprinkled sand on the hissing bomb with a shovel from the sandpit. When I expressed my surprise at this, she said calmly: “That’s how we learned it in the preparations”, which made a big impression on me. Soon afterwards, Marceline went to Feldenhofen for safety’s sake when I had advised her to do so, saying: “Go ahead, we survived the first world war well in Feldenhofen, we’ll do the same in the second”.

Serious decisions were made in the Bertele family: Hans decided to stay with Siemens and thought it would be best and safest for Marceline and the children to move to the Feldenhofen estate, which belonged to his mother. Feldenhofen, an estate of around two hundred hectares, mainly woodland, was located in southern Styria, which had to be ceded to the newly founded Yugoslavia after the First World War. However, this relocation would have to take place without the German children’s nurse Lena. In short, Lena was either dismissed or left the family at her own request. Although Marceline happily gave birth to children, apart from breastfeeding them, she had no idea how else to look after a baby. This task had always been carried out by the nursery nurses. Now, however, poor little Ursula became rickety and suffered constantly from diarrhea. So the decision was made not to take her to Feldenhofen, but instead to send her to Grandma (Marceline’s mother Emy) in Gaaden, where she was lovingly taken in and placed in the capable hands of nurse Nana.

So Marceline moved away with just five children to Feldenhofen, which was located near the town of Windischgraz, now Slovenj Gradec. At first, Marceline was still able to enjoy a peaceful and carefree life there and the children were able to run around freely and carefree everywhere. Then came 1945.

After an adventurous journey, which is described in detail in his memoirs, Hans only arrived in Yugoslavia in September and was shocked to learn that his wife and children were being held prisoner by the Tito partisans in a camp near Cilli. Typhus and hunger had reigned there. It was a true miracle that Marceline and all five children survived. Hans, who spoke Slovenian, a language very similar to Russian, was able to communicate with the camp commissary and gave her the English lessons she wanted from him in return for a favor. This enabled him to “work” for the release of Marceline and his children. The camp commissary was no longer able to use her newly acquired knowledge of English; shortly afterwards she shot herself. But thanks to God and her, the family was released again.

They drove back to Feldenhofen. However, well-meaning neighbors and former servicemen advised them to leave Slovenia quickly. With a heavy heart, the family finally set off again just after Christmas, on St. Stephen’s Day 1945, sneaking away via a smuggling route that Hans knew. A border stream, which was constantly patrolled, had to be crossed. Everything went smoothly. When we reached the hill, on the bank on the Austrian side, clearly visible from the Slovenian side, Marceline stopped and exclaimed aloud with great relief: “Well, if I had known it would be so easy, I could have taken more stuff with me!” If the patrol had suddenly appeared at that moment, they would have shot them all. It would have mattered little that they were already on the other side of the border stream.

The family was kindly taken in by Uncle Harald Reininghaus, Grandma’s half-brother, in Isenrode Castle (Styria). In February 1947, the little straggler, Uly, was born. When Marceline went into labor, she was brought to the clinic in Graz by sledge through the heavy snow.

In August 1947, the Bertele family moved on to England, where Hans had founded an electrical company with an English acquaintance.

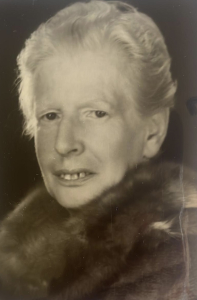

Ursula, the Gaadner child, only met her parents shortly before her departure. Until then, she had at least received a postcard from her mom once, with two deer in a snow-covered forest, which she still treasures. Now Nana sent her down the slope from the house on the mountain, where a path led to the village: “The two people you’ll see coming up the slope are your parents. Run down and say hello to them.” What happened would be a story in itself. Then I saw them for the first time. With their hiking boots, short socks, each with a rucksack on their back, they came towards me. They were 46 (Marceline) and 43 (Hans) at the time and seemed terribly old to me. Especially dear Mummy because of her white-blonde hair. In this context, it’s interesting that I’d never thought so much about age before. Both Grandma and Nana were simply timeless to me.

A few weeks later, I was taken to England and the new baby, Uly, called Jolly to distinguish him from Günther-Uly (son of Marceline’s sister Charlotte), was left with Grandma in Gaaden and given into Nana’s care. A child swap, so to speak.

The twelve years we spent in England were probably the hardest of her life for Mutti, as I will call her from now on. Baba (as Hans wanted to be called by us children) had bought a beautiful house with a large garden with an advance from the newly founded electrical company, which Mum liked very much. But the work there was immensely difficult for her, especially the laundry, as there was no washing machine. She boiled the whites in a large electric kettle in a room downstairs next to the kitchen, which served as a laundry room and general storage room for garden tools and other things. She then had to rinse and wring out the laundry by hand. During the school vacations, the four of us girls helped out and then hung them up on the washing line at the tennis court. Otherwise Mum did everything all by herself. However, with the frequent English rain, the washing always had to be brought inside quickly and then hung up again at the next opportunity. There was no way to dry them in the house. My eldest sister Emy was a great help to my mother. She was sixteen years old when we moved to England. She helped with the cooking and sewed clothes for Liesl and me. Marci, the second eldest, helped with the ironing and outside in the garden, she was also responsible for cutting back the hedge. With more than half an acre of land, that was no easy job. Liesl, and later me too, were put to work darning the socks, of which there were more than enough. We were also both tasked with washing the dishes. At the weekend, all the children had to help out in the garden. It was on a fairly steep slope. The house was on its lower third. Mom had had a vegetable garden planted at the top. Otto and Hansi tilled the beds for her. Mom also had her chickens up there and we had rabbits that our sister Marci looked after. We had a washing machine from around 1955, but it didn’t spin. Instead, there was a “wringer” that was attached to the sink and had to be started by hand. Over time, Baba also bought a car. The first one was very soon run over by my sister Marci. I, 14 years old at the time, was the co-pilot, which nobody was allowed to know! Baba then sold his most valuable watch to be able to afford a new one.

We four girls all went to the same convent school, which taught both primary and secondary school. Mom once told me that the headmistress, nun Mother Mary John, had told her about a dream on her first visit: a family from devastated Central Europe would come to England and the parents would ask her to accept their four girls into the school. She was told in the dream that she should take them all in – which she did with great affection. It goes without saying, I think, that this did not impose any major costs on the parents at this excellent private school. Mom sometimes said in her own way: “I’m not pious”, by which she apparently only meant that she didn’t go to church every Sunday. But on the occasion of the dear nun’s dream, she thought it was a miraculous providence of God. Mother Mary John was from a Belgian order, so Mummy must have communicated with her in French, because she didn’t speak English.

The best thing for us children was that mom was always there for us. She was always at home for us, so to speak. She was there in the morning, made breakfast for us and ate it with us. When we came home from school, she made us a snack. When the youngest members of the family were more independent, we prepared our own snacks, but first ran up to the garden to greet our mother, who was busy in the vegetable garden or with her chickens.

What a sad contrast to this is offered by mothers today, who just want to work somewhere away from home during the day, even if they don’t need to. The result is a limping, often dysfunctional family life and – often none at all. Everyone for themselves…

Mom always gave each of us all kinds of loving and special gifts. I will only mention the ones that she gave me and that I remember so gratefully: Of course, I didn’t speak a word of English at the beginning. Mom, although she was swamped with work, bought me a big picture book especially for me, which was about a little boy in Mexico. We would sit together at the big table in the kitchen in the evenings, me on my mother’s lap and she would read it to me: “Pedro was a little boy…”. There was the picture of Pedro and a loaded donkey next to a cactus. And I read it haltingly. When I was eleven years old, my mother arranged an exchange for me with the Gustav Harmer family, who were friends. The younger son, Conrad, the same age as my brother Hansi, came to spend a month with us in England and I was able to spend the whole month of July with the Harmers, initially in Ottakring and then mainly outside in Spillern. The youngest daughter, Mette, was my age. Everything was so beautifully arranged for me by my dear mother. In 1956, a famous concert performance of Don Giovanni took place in London at the Royal Festival Hall. Our relative, Eberhard Wächter, sang Don Giovanni. It was also special for me when my mother took me to the opera at Covent Garden for Cavallería Rusticana and I Pagliacci. And much later, when we came to Vienna for a visit, there was always a cyclamen cane in our room to welcome us…

A year and a half after we moved to England, little Jolly was sent to us, much to mom’s delight. Her little nestling. He was sent to us together with a Styrian girl who was to serve partly as a nanny for him and partly as general household help for Mummy. She was good for neither and left us after just one year.

A few years later, extremely difficult times had dawned for Baba and unpleasant years began in England. The starting point was a serious disagreement with his English partner, who falsely accused him of fraud. Far from home, everything seemed to be turning against him. He no longer knew what to do and was close to giving up the fight. But his mother encouraged him: “Hans, fight to the end. Only then will I have full respect for you. Let’s risk what you think is the worst-case scenario.” The matter was resolved in his favor, of course, when he left the company.

Austria was still occupied by the Allies at the time. Vienna was partially occupied, but Lower Austria was completely occupied by the Russians. His parents therefore preferred to stay in England with the family. With a new start in his career as a consulting engineer, Hans had too few orders and gratefully accepted the position of lecturer at Woolwich Polytechnic. Lectures often lasted late into the evening and so he came back from London by train, dead tired and exhausted. Every evening, Mum would set off to pick him up from the station. Although we only lived ten minutes away, the walk there was rather scary. You had to walk along a steep unlit cliff on the North Downs, which was opposite the wide track system, the passing places for the trains and a coal wholesaler. And so it went for a few more years until the good news finally arrived that Baba had been appointed Full Professor of Industrial Electronics at the Vienna University of Technology. The joy with which my mother received this news was indescribable. When she left England and stood on deck on the boat to Ostend, she said: “Thank God. Now I’m finally no longer a miserable foreigner!” The nice thing about England, she thought, was that she could always be there for her husband and children. Everything else had remained foreign to her. She had only learned to speak the language very poorly and her accent had remained strong. She also hadn’t made any friends. There was always a lively social life at home with frequent lunches and dinners at the weekends, but all those who came were friends and acquaintances of Baba.

In Vienna, the parents moved into the beautiful large apartment on Franziskanerplatz 1. They were both able to spend a little over twenty happy years there. There were constant visits from children and grandchildren and they were surrounded by nice servants. There were always lively and interesting lunches and dinners for mother’s extended family (Hans was the last descendant of the Bertele family) and the large circle of friends. There were also often events at the university to which the ladies were also invited. Marceline was always very proud of all the honors bestowed on her Hans. At home, there were lovely chamber music evenings where Hans played the piano accompanied by two violin-playing friends. Throughout the year, Hans loved to play before or after dinner on the beautiful large Bösendorfer grand piano that Marceline had given him as a wedding present. Marceline would sit in the salon au coin du feu – whether the fireplace was lit or not. And during the breaks in his playing, she used to say: “Very nice, Mr. Mandi” (her pet name for Hans).

![]()

With great love and gratitude, your daughter Ucki