Manfred I and the “Karl Schranz Affair”

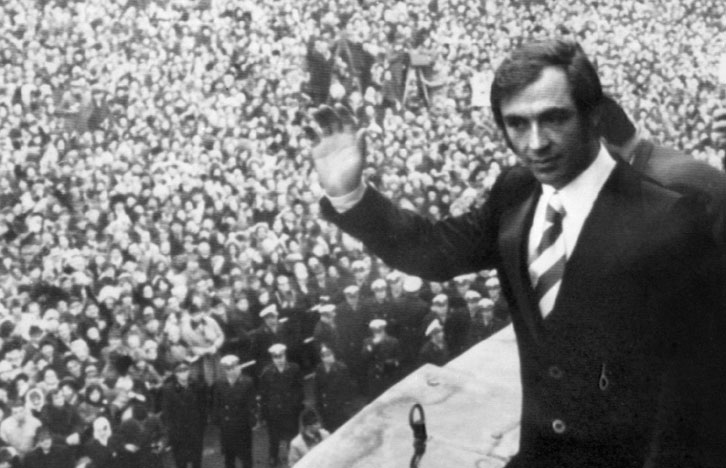

On February 8, 1972, around half past eleven, the Austrian Airlines’ DC9 “Niederösterreich” lands with skier Karl Schranz at Vienna Schwechat Airport. When “Schranz sees the crowd waiting for him for the first time, his eyes light up. He sits up and straightens his tie”, writes Alfred Kölbel in the “Arbeiterzeitung”. “And there, on his black Olympic jacket, flashes a silver star – the logo of his ski supplier.” He arrives from Sapporo and 200,000 Austrians cheer him enthusiastically. A few days earlier, at the instigation of President Avery Brundage (1887-1975), the IOC had barred him from participating in the games with 28:14 votes. Schranz had violated the amateur athletic rules, that prohibited amateurs from making financial profits from their sporting activities. In the morning of the crucial IOC meeting, Brundage had received Japanese newspapers, in which Schranz advertised coffee. Since then, the Tyrolean has been seen as the victim of a persistent idealist. By the leading Austrian populists, Hans Dichand (publisher Neue Kronen Zeitung) and Gerhard Bacher (Director General of the Austrian public broadcaster ORF), the exclusion of Schranz was qualified as an unfair injustice and used for a hate campaign against the IOC. Schranz had fallen victim to the arbitrariness of an old backward man, as they proclaimed, and “Austria” would not put up with that. After all, one would have to admit, that practically all skiers are professionals, not to mention the amateurs of the Eastern Bloc who are more or less employed by the state! Minister of Education Fred Sinowatz asked the Austrian Olympic Committee (ÖOC) to withdraw the entire team from the games. The ÖOC and the Austrian Ski Federation (ÖSV) rejected that. The people’s soul was boiling. Manfred Mautner Markhof, as IOC member, had sent Brundage a letter of acceptance before the expulsion because he wanted to create a favourable atmosphere. That so-called “disgrace” led to Mautner Markhof’s mustard boycotted and his grandson being beaten up at school. Schwechater beer was reviled as “Judas beer”. ÖSV President Karl Heinz Klee had to take his daughter out of school because her safety was in question. Schranz was chauffeured to the stoked crowd at Ballhausplatz in Sinowatz’s official limousine. There he was received by the Federal Chancellor Bruno Kreisky, who was uncomfortably touched by the “patriotic” feelings of the people. Schranz had to step onto the balcony three times, many of the enthusiasts had raised their right arms, which was for Kreisky too strongly reminiscent of the Nazi salute. He is said to have been so frightened by the media-induced hysteria that he changed the ORF law in 1974. The amendment cost Bacher the job.

Theodor Heinrich Mautner Markhof writes in his memories

My grandpa was appointed to several public offices. He was president of the Vienna Association of Industrialists, of the ÖAMTC, the Vienna Concert Hall, a senior official of the Chamber of Commerce and many other associations. As a member of the ÖOC (Austrian Olympic Committee), I think he was also its president, he put the whole family and me in a very strange situation. The Austrian skier Karl Schranz, who was very famous in the 1970s, apparently violated any rules of the Committee in 1972. The Olympic Games were purely an amateur event, and Mr. Schranz was sponsored by someone for money. Therefore, he was excluded from the winter games in Sapporo, unfortunately on site. This led to a national catastrophe, because television, ORF, extremely heated up the mood towards alleged injustice. The then World President of the IOC, Mr. Brundage, presented the journalists with a telegram from my grandfather with the following content, “I congratulate you on sticking to the Olympic idea.” Now the Austrians had found another “culprit” who could be held responsible for the fact that their idol had been that disparaged. That is how media hatred against my grandfather or rather everything that bore the name Mautner Markhof began. The phone at home was hot, strangers insulted us the worst. We also received bomb threats etc. At school, I was in the 5th grade at Hegelgasse, the students in my class were very nice, but all the other schoolchildren were less. When I thought I had to take my grandfather´s side and defend myself against the allegations, I had to take a lot of beating. I can still say today that I am still convinced that he was right on that point and Mr. Schranz was wrong. The people’s soul, however, was so stimulated by the ORF that Karl Schranz, who had to leave Olympia prematurely, was received like a state guest in Vienna. He landed in Schwechat and was brought to Ballhausplatz in an open limousine, the then Federal Chancellor Bruno Kreisky was also forced to put on an act. At that time, the route from the airport was via Simmeringer Hauptstraße and Rennweg towards the city centre. Crowds of people cheering Mr. Schranz wildly lined the way. So many people had gathered there before only for Hitler´s legendary appearance. All that had strange consequences. The first consequence was that the Austrians refused to buy our products. This situation only calmed down when the media stopped insulting us or my grandfather. Only slowly after one, then a little more quickly after two more months, the sales figures began to recover and finally paradoxically resulted in one of the best financial years in our family history. The lesson I learned from that story is that negative advertising also means advertising. If you can survive the period in question, it is even possible to make profit with its help. As a second consequence, we benefited from the chancellor’s seeming extremely uncomfortable with the excitement and crowds. As he was of Jewish descent himself and had seen the Third Reich, he had good memories that media power once out of control could also mean danger. So after a while he removed the former ORF director and changed the ORF law to prevent such situations in the future. Third consequence – I no longer believe the media at all, because the media spread opinions, but not the truth in the sense of objective facts. Nothing has changed to this day.