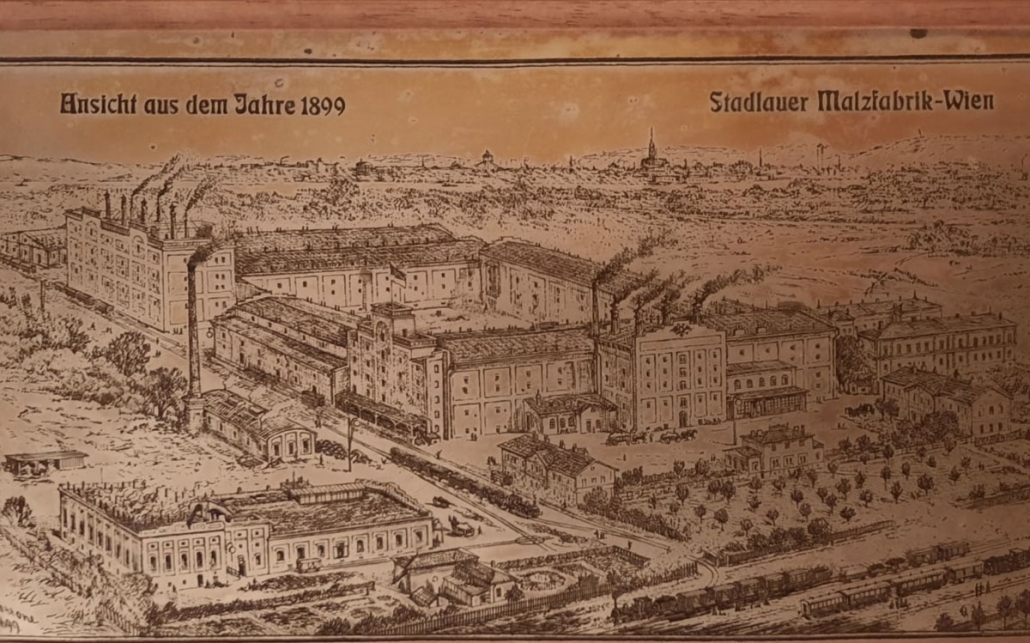

In 1938, the Mautner Markhof family acquired the majority shareholding in HAUSER & SOBOTKA AG, which for decades had not only distinguished itself through the distribution of the baking agent DIAMALT “all over the world”, but also maintained a laboratory that was primarily active in baking science. In addition, the production of enzymes (alpha-amylase from pig pancreas) had already begun by a specially hired chemist (Dr. Bader). Now, the new main shareholder, with his flagship Schwechat Brewery, saw himself primarily as a brewer and in his considerations with the takeover of Hauser & Sobotka had only bought a malt factory, which was also reflected in the new company name.

The Diamalt department, on the other hand, although the Diamalt brand certainly had the highest level of recognition in the industry worldwide at the time and the laboratory in Stadlau had also been a competence center for relevant specialist knowledge since the beginning of the century, was seen as nothing more than a practical “appendage” to which the Sekunda-Barley was processed, which reduced the extract content of the brewing malt. The laboratory’s function was reduced to operational analyzes (malt, soup seasoning, Diamalt), leaving it the only thing left of the once proud bakery company. When the two bakery scientists from Hauser & Sobotka left, their knowledge was also lost and the new main shareholder no longer showed any interest in the matter. The technically experienced chemist Huber, who was hired back in 1949, no longer focused on basic research, but instead concentrated on getting the quell flour production going.

There were no economically serious competitors at that time. The BOEHRINGER company has already appeared as a baking aid competitor with a number of by-products, including ROPAL as an anti-stringing agent. Since this product was protected by patent and stringing was a major problem for Austrian bakers at the time, Boehringer was able to gain a foothold in bakeries with this product. In return, we managed to get an Austrian patent for the FADENSICHER in order to stand up to this competition. A timid attempt by the KNORR company with the malt flour MAXIMALTIN passed without harm in 1951. Small disruptive factors in the sales markets continued to spread from time to time: in 1952, the HUBERTUS brewery in Laa an der Thaya started producing diastatic baking malt extracts and supplied bakeries in the area. Across Austria, the small malt factory SALVATOR-Malzkaffee GmbH Deri & Co disrupted unhindered Diamalt sales with the baking malt extract SALVOMALT. So it was decided to acquire this brand and the malt extract production facilities in the 1953/54 financial year. Since no competition was expected from the malt production facilities, they were left out of the purchase – which would have bitter consequences years later.

1953 was the year when competitors completely surprised everyone with their products. It was the companies Boehringer and IGLAUER that brought citric acid-containing dough leaveners (ULMER BROTHILFE/Iglauer, BOEROL/Boehringer) and “dry” white pastry baking agents enriched with lecithin (MEISTERGRUSS/Iglauer and MULTIN/Boehringer) onto the market. Boehringer was represented in Austria by the company BENDER & Co, which was primarily known as a sales company for Boehringer’s pharmaceuticals. The Iglauer company was founded by the chemist of the same name, who worked in the baking products department of Boehringer/Germany during the war.

He had been the inventor of the anti-stringing patent mentioned above. Dr. Iglauer was Austrian and had returned to his native Carinthia and was a licensee of the German company ULMER SPATZ (EISELEN). Ultimately, the founding of the Iglauer company was also the birth of the later successful baking products company AUGENDOPPLER, because Alois Augendoppler began his work as sales manager for this company. At STAMAG it had to be recognized that these companies had specialist knowledge that they themselves did not have. You were completely helpless in the face of the situation and, for example, completely surprised that Protosauer could also be used to produce a mixed wheat bread. There was no equivalent technical know-how, no marketing and, above all, no one who recognized this danger or knew how to assess the situation accordingly.

Two factors were intended to prevent STAMAG from being pushed out of the baking products market at that time. On the one hand, the lecithin-containing baking products could not yet score decisively against Diamalt because the guides for small wheat baked goods that were common in Austria at that time (indirect guides = Dampfl, as well as long guides with dough resting for at least two hours) resulted in very high dough stability and The “emulsifier” effect of lecithin therefore had little effect. The decisive stroke of luck, however, was the entry of Dr. Karlmann Mautner Markhof, on August 1, 1952, who was brought in to replace the retiring sales manager and was the only one in the company who recognized the full extent of the problems. After his training period at Diamalt-Munich, he took over management of the baking products department, which until then had more or less languished without proper leadership. By building a powerful sales organization and using intensive advertising, Karlmann was not only able to support sales of baking products, but even increase them. With DIAMALT SUPER they created a product that was far superior to all competing products. Unfortunately, a short time later, the emulsifier used for this was banned from food use in the USA. So this emulsifier had to be replaced with lecithin, although there was no danger from competing products. The existence of the baking products department was not only secured, but it was even expanded in 1956/57. A test bakery meeting the requirements was set up and a specialist teacher was hired as a master baker. DIAGOLD, a “dry” mixed baking agent for wheat dough, was immediately brought onto the market. Subsequent research into enzymes and emulsifiers also gave cause for thought. If emulsifiers and highly concentrated enzymes were to play the decisive role as active ingredients in baking agents in the future, then the current dominance of malt as an effective component would come to an end and STAMAG would also be dependent on purchasing these “new” active ingredients. Competition would be expected to become more intense, as every company could acquire the same technical know-how, which in turn would make it much easier for newcomers to get started. The focus was on counteracting this by deciding that the baking products department would have to counteract the threat of increased competition by expanding.

This is how HEINZEL-Nahrmittel GmbH was founded. The idea behind it was to first attract the market’s attention with convenience products that were new to Austria and then to offer high-quality “kitchen products” to restaurants and households. To get started, ready-to-cake flours like those commonly used in the USA, pudding powder (the FLANA quality later created by OETKER), meat tenderizer and ice cream powder were developed. Even the start was not a lucky one. It turned out that the “Heinzel” brand was already protected for INZERSDORFER NAHRUNGSMITTEL GmbH. The brand was purchased and the managing director of this company, Mr. Petrusch, was given a seat on the supervisory board of the Stadlauer Malzfabrik. There was time pressure because it was very difficult at the time to find a mill that could and would produce the special quality necessary for cake-ready flour in the small quantities needed. As a result, it was not possible to match the “visibility” of the cakes to the USA quality at the time. However, it was hoped that better flour would also achieve better volume. The market launch was carried out by DIE HAGER, the agency headed by Manfred II Mautner Markhof, and sales got off to a good start. The cake mixes found their way into the catering industry relatively quickly, but understandably more slowly into households via retail outlets. There were practically no problems with complaints. Raw materials, machines, packaging and advertising materials for the upcoming products were already in-house when the parent company suddenly ordered Heinzel to shut down. The reason given was the high losses that had occurred. At the end of August 31, 1956, the files showed a loss of ATS 1,673,372.63, but there was also a lack of understanding among the workforce and on the part of Karlmann Mautner Markhof as to why they had expected to cover the start-up costs and the expensive sales organization with the proceeds of the very first product.

Unaffected by these problems, the defensive battle against the ever-increasing competition continued in the baking products department, but under improved conditions. With great personal commitment, Karlmann had built up an enthusiastic, effective sales organization and the specialist knowledge was now state-of-the-art. The competition had not succeeded in making a breakthrough in the Austrian (white biscuit) market; sales levels were maintained for many years. Two factors secured the position as “top dog”: The better quality of products and customer service. The better product quality resulted from the fact that at the beginning of each new wheat harvest, the expected flour quality was researched in detail and the product recipe was adjusted accordingly, while the competition with a standard recipe did not always correspond so well to the characteristics of the raw material, which were mostly fluctuating at the time. The advantages of customer service, on the other hand, came into play in the (rye) bread sector when rye growth damage frequently occurred in the 1950s. After submitting a flour sample and announcing how to use the dough, the baker received precise instructions on how best to process his flour.

In 1962, Karlmann received assurances from HUBERTUS BRAUEREI that, with a few exceptions, they would withdraw from selling baking malt extract. An overview of the most important products developed up to 1967: Ice cream powder was continued in 2 different variants (soft ice cream/spade ice cream machines), in different flavors and the COLD JELLY product was at the beginning of the production range. In the mid-1960s, the production of glazes and tunk masses began. The production of baking powder and vanilla sugar arose naturally as business relationships with confectioners became closer.

In the meantime, more and more bakers switched from the Diamalt baking malt extract to the dry product Diagold, which meant that from then on it was easier for them to switch to a dry product from the competition. From this point on, STAMAG was involved in unusually difficult competition, which did not yet have a serious impact on sales. The “release agent” (for products baked on trays) CARLO from the Dutch company ZEELANDIA, which was brought onto the market in 1964, brought good business over the years.

The domestic brewing malt market had meanwhile become increasingly worse for STAMAG. As mentioned, when purchasing the Salvator extract plant it was decided that the small malt factory would be uninteresting as it would never represent real competition. But this malt factory sold so well at full capacity that its owner was able to build a new one at another location that was, according to the LAUSMANN system, more modern than that of STAMAG. In the group, however, resources were not pooled. While the malt factory in Stadlau was only modernized in small steps, a new one was built in Schwechat at the same time. MAUTNER FERMENT was also developed in Simmering, a competitor product to baking products.

In 1968/69, baking agents with a synthesized emulsifier (a diacetyl tartaric acid ester of fatty acid glycerides) appeared for the first time in Austria. STAMAG introduced its GIGANT emulsifier baking agent without any problems. The sales figures for white pastry baking products were still maintained, but only with significant losses in earnings due to the price pressure from competitors. The sale of confectionery products was a great success and the high sales of ice cream powder, icing and dipping mixtures made a spatial expansion necessary. For tunk masses, a production line was implemented from the raw bean up to and including the roasting stage. The first 53 tons of chestnut puree were sold in 1972/73.

At the beginning of the 1970s, the company’s management initiated intensive meetings with the IREKS-ARKADY company, which ultimately ended in the sale of the majority shareholding to them.

The sale of the Staudlau malt factory

prepared by Viktor Mautner Markhof

The so-called “four-man group”, which consisted of two representatives each from the lines of Theodor I and George II, determined the business since the 1930s and, by agreement, occupied the top management positions in the family businesses in Schwechat, Stadlau and Simmering. These were Gerhard and Manfred I and George III and Gustav I.

At the Stadlauer Malzfabrik, which was acquired in 1938, the descendants of the Theodor line, namely Gerhard as chairman of the board and Manfred I as chairman of the supervisory board, initially held the leadership roles. Other family members also held simple supervisory board positions. At the beginning of 1966, a family agreement was signed to initiate the transition from the older to the younger generation, particularly in operational business. This resulted in Gustav I being appointed chairman of the board of STAMAG for a short time in mid-1966, but from 1968 onwards Heinrich, and Karlmann was also appointed to the board.

Gerhard replaced Manfred I as chairman of the supervisory board, with George III, then Gustav I and finally Gustav II succeeding him in this role after his departure. There were similar regulations for Schwechat and the companies in Simmering. At the beginning of 1970, at a time when all of the old members of the foursome were still alive, George III began to prepare a proposal for a new family agreement. In the future, the chairmanship and deputy functions on the boards of directors and supervisory boards of the individual companies should be determined for Heinrich, Manfred II, Gustav II and George IV. Other male family members were not even considered. Unfortunately, Gustav I died in October 1970 and Gerhard in March 1971. So within a few months, two members of the “old” foursome were no longer alive and the influence of the two still living seniors on all important decisions was even greater.

As far as STAMAG was concerned, George III took over – as agreed in 1966 – the chairmanship of the supervisory board. Heinrich as chairman of the board and Karlmann as board member retained their functions.

In the main malt division, STAMAG dominated the Austrian market in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and in the baking aids and confectionery product division, which was headed by Karlmann, it now had an impressive market share of around 50%. The malt division contributed around 58% of the company’s sales of 160 to 180 million schillings, the baking aids and confectionery products the remaining 42%, although in terms of results the malt division was in the foreground, as it generated around two thirds of the total result. The net profit reached almost two million schillings annually without releasing reserves, in part despite greatly increased early depreciation, especially in the baking aids and confectionery product division. In terms of balance sheet and liquidity, the company was, in any case, according to Georg III’s assessment. “very good to excellent” there.

Nevertheless, George III began, shortly after taking over the chairmanship of the supervisory board, to think about selling the baking aids and confectionery products division. He justified this with the penetration of large German corporations into the Austrian market, including the Ireks-Arkady company. For the malt division, he envisaged a merger with Schwechat or a sale. He was concerned about STAMAG’s comparatively small size compared to its German competitors and the associated cost disadvantages, as well as the possible replacement of malt with enzymes.

Understandably, Heinrich was not convinced of the usefulness of this approach, not only as a person directly affected, but also from an economic perspective. Even other family members, such as George IV, Manfred II and Marius, were irritated. Karlmann, on the other hand, who viewed the development of baking aids and confectionery products as having great potential and did not rule out the possibility of continuing the business of his division in a new joint organization, was positive about the request. Unsurprisingly, this resulted in violent arguments within the family.

From a neutral point of view, those feared challenges cannot be dismissed out of hand, but, they could certainly have been overcome with appropriate investments and merging activities with the Schwechat and Simmering companies.

But now Schwechat and Simmering also found themselves in the situation of having to either invest in themselves for future survival or find a partner in order to be prepared to face Austrian and European competition in the medium to long term. The first steps had already been taken, but without success. In Schwechat, merger negotiations with Brau AG were broken off in 1969 – due, among other things, to different views on running a joint company and reservations on the part of Creditanstalt – and subsequent discussions with the Styrian breweries also failed. In addition, the Mautner Markhof family in Schwechat was dependent on the participation of other shareholders, including the Creditanstalt. With the yeast division in Simmering, no major Austrian solution was achieved, apart from the merger with Wolfrum in 1971.

In 1971, Georg III began negotiations with the German company Ireks-Arkady, which was interested because it was already pushing into the Austrian market. At the end of December 1971, he outlined in a note the plan to merge STAMAG with the Schwechat AG brewery and then sell the baking aids and confectionery division to Ireks-Arkady, with a sales price of 35 million schillings being considered.

So far so good. Nevertheless, the question arose as to how sensible it was to sell a division in which, after years of effort, we had finally achieved a market share of 50% and which – even if it was not yet sufficiently profitable at the time – seemed quite capable of expansion, and at the same time in a sister company to continue operating a similar division in Simmering, more or less like a competing company. From the perspective of the Simmering companies, Georg IV therefore considered buying the baking aids and confectionery products division on the same terms as Ireks-Arkady and integrating it into Simmering. However, he did not pursue them any further; the seniors rejected it – much to his regret, as he would find out years later.

At the end of 1971, STAMAG’s share capital was 18 million schillings. 30% of this was held by the Schwechat AG brewery, 21% by Michael MM and 20% by the Vereinigte Hefefabriken Mautner Markhof and Wolfrum. The remaining 29% were in free float. The market value was around 250% of the nominal value, i.e. around 45 million schillings.

The negotiations with Ireks-Arkady for the sale of the baking aids and confectionery products division dragged on for months during 1972 and when they were almost completed, an auditor’s report in October found that the sales proceeds were 35 million schillings would be reduced by taxes to be paid amounting to around ten million schillings, i.e. by around 30%.

This was unacceptable. The sales strategy therefore had to be changed and a different proposal developed. In mid-November, Georg III finally offered the Ireks-Arkady company the sale of around 75% of STAMAG’s share capital at a price of 300%. This corresponded to approximately 40.5 million shillings.

Given the current share price of around 250%, this seemed like a good deal, although a higher price would have been justified. Estimates that the company’s intrinsic value reached a good 500 – 550% were apparently ignored. The twelve hectare property in Stadlau alone was worth 50 – 60 million schillings, the expected annual cash flow was 8 – 10 million schillings and the annual income value was around 5 million schillings. Taken together, this was well above the 300% offered and would have justified a rate of 500%. Even if the individual divisions had merged with Schwechat and Simmering, a considerable additional profit could have been achieved through rationalization measures and from the sale of the Stadlau area.

But the juniors in the family were apparently unable to dissuade the seniors – especially George III – from their plan or to demand a higher selling price. Unless other economic or tax aspects, personal reasons or perhaps a lack of trust in the younger generation were decisive, there was probably a misjudgment of the situation and, above all, the potential. Perhaps the old generation also lacked the strength to transfer the courage that they themselves had shown more than once before and after the war to the younger generation in order to face the challenges and oppose the sale.

The Ireks Arkady negotiators responded to the new offer at the beginning of December by saying that they were actually not interested in taking over the malt business because they judged the future of this division to be very unfavorable if the existing protective tariffs were lifted. An extremely clever argument, especially since they knew very well about the high value of the Stadlau property, the positive earnings value of the malt division and the expected cash flow. The offer of 300% was also not questioned, which should have been enough of an indication that the valuation was too low. Even if Ireks-Arkady had closed the malthouse, with or without taking over the volumes into its own operation, which also had free capacity, it would not have had a negative impact. The takeover of the baking aids and confectionery products sector with a 50% market share in Austria, which was originally the starting point for all negotiations, suddenly seemed to be a minor matter. Based on previous negotiations and commitments, Ireks-Arkady assumed that it had already acquired the baking and confectionery division, even if there had not yet been a formal sale.

Due to a previously unaccounted transfer of provisions in the course of a sale, it was determined that the effective purchase price was not 300%, but 324%. Ireks-Arkady suddenly claimed that he could only expect his shareholders to pay a price of 300%. They also demanded that Heinrich and Karlmann leave the board quickly, with Georg III bringing up possible continued employment for his brother Karlmann in the negotiations. In any case, Georg III himself should continue to exercise his role as chairman of the supervisory board until the transaction is completed.

Heinrich not only felt inadequately involved in George III’s negotiations, but he was also faced with facts that were detrimental to him, even though he had been assured by the foursome that he would not have to accept any financial disadvantages. He therefore expressed his dissatisfaction in an official letter in December 1972 and was forced to demand his claims from the existing contracts with the help of a lawyer.

On February 3, 1973, Georg III signed a contract in Munich with an offer at a rate of 300%, which sealed the sale of STAMAG (only the approval of the National Bank was pending), and an additional agreement that regulated the personnel. The latter stated that Heinrich and Karlmann should mutually resign from the board at the end of May. It was also promised to elect two Ireks-Arkady representatives to the supervisory board at the next general meeting in March.

At the end of February, Heinrich received at least an assurance that he would be allowed to join a subsidiary of the Schwechat brewery as managing director after leaving STAMAG.

On March 5, 1973, the general meeting took place at which the two representatives of Ireks-Arkady were to be elected to the supervisory board. There was a scandal when Heinrich’s brother Marius, who exercised the shareholder rights for himself and Heinrich for their small blocks of shares, refused to consent to this election, pointing out that he did not recognize the additional agreement signed at the beginning of February that provided for this election. The reasons he gave were that, on the one hand, George III’s promises regarding compensation for Heinrich’s departure from the board had not yet been fulfilled and, on the other hand, Marius had not been informed at all about the documents signed by George III at the beginning of February. Although his refusal had no bearing on the outcome of the election, it still agitated people. George III saw the outstanding approval of the National Bank at risk. He therefore threatened Heinrich with immediate dismissal from his board position and Marius with claims for damages if they did not immediately make a statement acknowledging the contract and the additional agreement of February 3rd.

The mood between George III and his nephews had reached a low point. The correspondence went through the lawyer and direct written addresses were temporarily only made in the third person. Nevertheless, both Heinrich and Marius agreed to the agreements of February 3rd at the beginning of April. Shortly afterwards, George III tried to smooth things over in a letter of reconciliation, but this did not change the already severely disturbed understanding of the family.

At the end of April, the National Bank granted its approval. At the end of May, Heinrich and Karlmann resigned from the board. Heinrich moved to Schwechat and Karlmann to Simmering. The new family agreement, which George III had been working on in 1971, never came to fruition.

Although George III had achieved his goal of selling STAMAG – for whatever reasons – he had done a rather questionable service to subsequent generations of all lines of the family. Unfortunately, the successes of STAMAG predicted by the opponents of the sale proved those who had spoken out against it painfully right in the years that followed.